My alternate history murder mystery “Under the Shield,” featuring Tesla and his technologies as major plot points is now available to read for free in the archives of Intergalactic Medicine Show. Check it out now!

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=

Now then, to begin this episode, we need to get in the WABAC Machine and do a little time travelling. Or at least a little time sorting, because as I mentioned a few minutes ago the chronology here is weird.

One of the challenges in trying to present the life and times of Tesla is to do so in a way and in an order that makes sense to us, now, looking back on the man’s life and work. Doing any kind of history necessarily involves sorting and ordering information in a narrative, telling it as a story that helps us make sense of event in the broader context of the man’s life in a way that he wouldn’t have been able to as he lived it. His life, just like yours and mine, was messy and a jumble of varied and competing tasks that all overlapped. Trying to narrate them that way as they happened would just be impossible to follow.

So, I’ve been jumping around a bit and, frankly, ignoring a few things temporarily as I sought to outline the War of the Currents (which still isn’t quite over, by the way) and get us through the Chicago World’s Fair. But what I’ve been ignoring is important to cover and that’s what we’re going to do today.

But as we talk today try to keep in mind that everything from this point on in the episode is happening in 1893 after Tesla returned from his European lectures in Episode 20, and while he’s helping Westinghouse prepare for the World’s Fair and then giving his show-stopping presentations in Chicago.

The events in this episode are also happening alongside Tesla’s participation in the Westinghouse bid to win the contract to harness Niagara Falls to produce electricity, which was also happening alongside World’s Fair business, and which we haven’t even mentioned yet and which will likely be Episode 26 or 27.

Basically, as you listen this time, just keep in mind that while it may seem like Tesla was just doing some leisurely experiments in his lab and giving the occasional lecture, he was actually insanely busy and trying to keep a lot of balls in the air with all these competing priorities, just like your life and mine.

So then, if you’ll cast your mind back to Tesla’s return from Europe in Episode 20, you’ll recall that he reopened his lab on South Fifth Avenue, hired some workers and a secretary, and got back to work.

So what was Tesla working on between World’s Fair business and the Niagara Falls contract bidding?

Well, he spent the winter of 1892–93 working on his high-frequency apparatus. This all came out of his recent European trip (which we covered in Episode 20). Remember that Lord Rayleigh had told him that he was destined to discover great things, and Sir William Crookes (in attendance at Tesla’s lecture) had suggested the possibility of using electromagnetic waves to transmit messages.

And there was one other element that had inspired Tesla’s new direction, which we touched on briefly at the end of Episode 20, that bears mentioning in more depth—as it shows Tesla’s grand vision for what would occupy much of the rest of his career (for good and for ill).

While Tesla was still back in Europe recovering from his breakdown after the death of his mother, he went hiking in mountains and got caught in a thunderstorm. , finding shelter just in time. As he described in his autobiography:

“[S]omehow the rain was delayed until all of a sudden, there was a lightning flash and a few moments after a deluge. This observation set me thinking. It was manifest that the two phenomena were closely related, as cause and effect, and a little reflection led me to the conclusion that the electrical energy involved in the precipitation was inconsiderable, the function of the lightning being much like that of a sensitive trigger. Here was a stupendous possibility of achievement. If we could produce electric effects of the required quality, this whole planet and the conditions of existence on it could be transformed.…The sun raises the water of the oceans and the winds drive it to distant regions where it remains in a state of most delicate balance. If it were in our power to upset it when and wherever desired, this mighty life-sustaining stream could be at will controlled. We could irrigate arid deserts, create lakes and rivers and provide motive power in unlimited amounts… The consummation [of this idea] depended on our ability to develop electric forces of the order of those in nature. It seemed a hopeless undertaking, but I made up my mind to try it and immediately on my return to the United States in the summer of 1892, work was begun which was to me all the more attractive, because a means of the same kind was necessary for the successful transmission of energy without wires.”

Thinking back to his experiments of Fall 1892 in which he grounded his oscillating transformer, Tesla now believed that if he could scale up that transformer he might be able to harness the Earth itself. And so Tesla set himself to discovering a way of using the Earth to transmit both messages and power. More on that in a minute.

Because first—and because he apparently didn’t have enough on his plate already—that winter Tesla also agreed to do more lectures: one before the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia on 25 February 1893 and another a week later at the National Electric Light Association in St. Louis.

While he was still months away from the true national fame that would come his was after the World’s Fair, Tesla was already attracting the attention of both reports and the public. He could not deny that in addition to technical achievement, on some level he also craved recognition for his genius and accomplishments. So while interacting with his peers was an inducement to taking on these lectures, they were also a means for Tesla to establish himself as one of the era’s preeminent men of electrical science—on par with Edison—both for his colleagues, the press, and a wider public. As we’ll see next episode, for a time Tesla would spend almost as much energy building and polishing his reputation in the press and high society as he did on actual invention.

At least as a time saver, the lectures Tesla gave were similar to what he had done in Europe, and acted as a kind of dry-run for the presentations he would give later in the year during his triumphant displays at the Chicago World’s Fair. Each offered “philosophical musings on the relationship between electricity and light along with sensational demonstrations.”

And Tesla—ever the showman—did not disappoint.

In Philadelphia, he started strong: passing 200,000 volts through his body. As he described in the published version of the lecture:

“My arm is now traversed by a powerful electric current, vibrating at about the rate of one million times a second. All around me the electrostatic force makes itself felt, and the air molecules and particles of dust flying about are acted upon and are hammering violently against my body. So great is this agitation of particles, that when the lights are turned out you may see streams of feeble light appear on some parts of my body. When such a streamer breaks out on any part of the body, it produces a sensation like the pricking of a needle. Were the potentials sufficiently high and the frequency of the vibration rather low, the skin would probably be ruptured under the tremendous strain, and the blood would rush out with great force in the form of fine spray… [T]he air is more violently agitated, and you see streams of light now break forth from my fingertips and from the whole hand. The streamers offer no particular inconvenience, except that in the ends of the finger tips a burning sensation is felt.”

Ruptured skin? Exploding blood? Burning finger tips? Oh, is that all? Its a wonder more people weren’t doing these kind of demonstrations…

The published text of the Philadelphia lecture runs a hundred typeset pages and covers a lot of ground, so we won’t cover it all here. Tesla reviewed different means by which electricity could produce light using electrostatics, impedance, resonance, and high frequencies. He once again pulled his lightsaber trick, spinning glowing tubes around the darkened theatre like (as one account put it) “the white spokes of a wheel of glowing moonbeams.”

Perhaps most notably in these lectures, Tesla—before anyone else—outlined in broad strokes the possibilities of wireless communication and explained (at least in rudimentary form) all the major components such systems would need.

More than a quarter century later in his autobiography, Tesla claimed that he encountered such opposition to his discussion of what he termed “wireless telegraphy” at that time that “only a small part of what I had intended to say was embodied [in the speech].”

Now, some in the more conspiratorial corners of Tesla fandom online will suggest that this opposition is yet another sign that Big Business interests and the power companies were trying to keep Tesla’s ideas down and torpedo Tesla’s plans for worldwide free energy.

In actuality, this opposition came from friends and supporters, primarily, and had far more to do with the underlying physics that Tesla was using to make his claims.

Tesla, as we’ve discussed before, was a believer in the nineteenth-century theory of the ether: an all-pervasive medium between the planets and stars.

More than a decade early, in 1881, a famous experiment by Michelson and Morely attempted unsuccessfully to measure the luminiferous ether. At the dawn of the 20th Century, Albert Einstein used the failure of the Michelson-Morley experiment as part of his argument for overthrowing the idea of the ether when his Special Theory of Relativity introduced the concept of space-time and proved that the idea of the ether was unnecessary for explaining how light and energy can travel through space. And, as mentioned, Tesla never ever, to his dying day, accepted the arguments for relativity, even after experimental proof has begun to be offered (such as, for example, gravitational lensing, not to mention the splitting of the atom which seems kind of definitive proof if you ask me…but I digress).

Anyway, in 1893 belief in the ether wouldn’t have been unusual or been anything that would get any one out of joint. Instead, what really got Tesla into hot water with his fellow engineers and scientists was his adherence to a theory that was marginal (and considered a bit crackpot) even in the 1890s. That theory was known as “Mach’s Principle,” after its originator Ernst Mach, who we met in Prague back in Episode XX, and who remained there, continuing his work.

Mach’s Principle shaped how Tesla understood the nature of the ether and how energy and electricity propagated through it. Mach’s Principle would also greatly influence Tesla’s theory about wireless transmission of power and how energy might be harnessed from and transmitted through the earth.

So what was Mach’s Principle? Well, while Mach argued for its scientific-ness, we can really only understand his principle as some kind of quasi-mystical worldview. Mach hypothesized that all things in the universe were radically interrelated. The mass of the earth, according to this theory, was dependent on a supergravitational force from all stars in the universe. There were no separations between things. Mach himself acknowledged this view’s correspondence to Buddhist thinking. I myself am reminded of that old joke: What did the Buddhist monk say to the hot dog vendor? Make me one, with everything.

It is all the more interesting that Tesla bought in to a theory with such clearly mystical implications given his professed materialism. It’s not, however, the first or last time we’ll see this tension displayed by Tesla. We’ll see much later in life Tesla adopt terminology straight out of Hinduism to explain his thinking about certain phenomenon. As I think I’ve said before, despite his professed unbelief, I think Tesla’s upbringing in the intensely religious household of an Orthodox priest—from a family of Orthodox priests, no less—shaped him in ways that were lasting, even if he was never a traditionally religious believer.

What got Tesla into trouble with his scientific peers (and what his friend said would scare away potential investors) were claims he made based on beliefs he derived from the Mach Principle that were too “out there” for scientists of his day to accept. The biggest one (and I don’t claim to understand the difference here) was Tesla’s claim that he could create electromagnetic oscillations that displayed transverse wave as well as longitudinal wave characteristics. The specific difference between the two isn’t important for our purposes (thankfully) other than to say that while transverse waves were well understood, the claims that Tesla made for longitudinal waves (that they carried much more energy than transverse waves) was based on the Mach Principle and was a bridge too far for his contemporaries.

In fact, as Tesla’s writing more than 25 years later demonstrated, he clung stubbornly to this belief for the rest of his life, despite all opposition to these claims (which came from just about everyone in the field).

Tesla wrote: “There is no thing endowed with life—from man, who is enslaving the elements, to the nimblest creature—in all this world that does not sway in its turn. Whenever action is born from force, though it be infinitesimal, the cosmic balance is upset and universal motion results.”

Now, to some degree this does play in to Tesla’s belief about humans as “meat machines” who generate none of their own thoughts or ideas, but instead are just responding to external stimuli. Thanks to Mach, however, Tesla now began to believe that these stimuli came from everywhere in the universe.

Tesla biographer Marc Seifer, who appears to himself be a modern-day defender of ether theory based on some of his other writings, spends a lot of time connecting Tesla’s work to the concept of the ether in WIZARD, his biography of the inventor. But I’m going to skip over all that content since I think the science is pretty solidly on the side of the ether not actually being a thing.

So, getting back to the lectures, we do see some of Tesla’s vision and prognostication come to the fore in these presentations, particularly regarding the finite resources of the planet.

Back in the late 19th Century (and well into the 20th, actually) virtually no one was thinking about or worried about whether we might run out of natural resources. This is understandable, given that humanity had only recently begun to industrialize, there weren’t nearly as many of us back then (there were only about 1.6 billion people on the planet in the 1890s), and most of those people didn’t live the kind of resource intensive Western lifestyle that so many of us are lucky enough to enjoy today. Heck, the American western frontier had only just finished being settled by American homesteaders. If anyone stopped to think about it at all, the world and its resources must surely have seemed inexhaustible.

Tesla, however, could take the longview in a way that many contemporaries couldn’t. And realizing that the world actually was a finite place and that the natural resources we depend on as fuel to produce electricity and power our lives and industry would eventually run out, he spoke out about it.

“What will man do when the forests disappear,” he asked his Philadelphia audience, “or when the coal deposits are exhausted? Only one thing, according to our present knowledge, will remain; that is to transmit power at great distances. Man will go to the waterfalls, [and] to the tides.” Tesla was an early proponent of harnessing renewable sources of energy.

And while tidal power and hydroelectric generators were all well and good (stay tuned for the next War of the Currents episode where we hear all about the harnessing of Niagara Falls!), Tesla (as usual) was dreaming bigger. He intended nothing less, he said, than constructing equipment to “attach our engines to the wheelwork of the universe.”

What exactly did Tesla mean by this? Well, this is where he tied in his ideas about the possibilities for wireless transmission of energy.

“I firmly believe,” he said, “that it is practicable to disturb by means of powerful machines the electrostatic conditions of the earth and thus transmit intelligible signals and perhaps power. Taking into consideration the speed of electrical impulses, with this new technology, all ideas of distance must vanish, as humans will be instantaneously interconnected.”

Tesla’s experiments were still in early stages so he didn’t yet feel he had a grasp of the electrical capacity of the earth or its potential charge, but he knew the size of the earth and the speed of light and that was enough to get him started theorizing about the optimum wavelengths for transmitting impulses through the planet.

“If ever we can ascertain at what period the earth’s charge, when disturbed [or] oscillates with respect to an oppositely electrified system or known circuit, we shall know a fact possibly of the greatest importance to the welfare of the human race,” he told the crowds. He also produced for the audience a diagram that depicted how to set up the aerials, receivers, transmitter, and ground connection for moving electricity through the earth.

“When the electric oscillation is set up,” Tesla said, “there will be a movement of electricity in and out of [the transmitter], and alternating currents will pass through the earth. In this manner neighbouring points on the earth’s surface within a certain radius will be disturbed.”

Tesla also noted that “theoretically, it [w]ould not require a great amount of energy to produce a disturbance perceptible at great distance, or even all over the surface of the globe.”

Tesla left Philadelphia by rail at the end of February for the National Electric Light Association convention in St. Louis.

Accompanying him was T. C. Martin, who we’ve mentioned before and who we’ll spend more time with in the next episode. Martin was covering both lectures for Electrical Engineer, and on the train ride, he proposed a textbook based on the inventor’s collected writings. The first half would be about the AC polyphase system, with chapters on motor design, single phase and polyphase circuits, armatures, and transformers; and the second half would be made up of Tesla’s lecture on high-frequency phenomena, that he had given in New York, London, and Philadelphia. Martin would write the introduction. The book—The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla—would eventually run almost five hundred pages and we’ll talk about it more next time.

On February 28, Tesla arrived in St. Louis to give his lecture and the city was vibrating with anticipation. The event was booked into the Exhibition Theater, but that venue proved too small given the interest in the event, so it was moved to the Grand Music Entertainment Hall, which seated four thousand. On that cold February night, however, the theatre was packed to bursting with several thousand additional spectators. Surely a fire code violation if ever there was one.

On the streets, “over four thousand copies of the journal containing [a] biographical sketch [of Telsa] were sold” to eager St. Louisans. (LOO-wi-SENS)

The demand for seats to the event was so great that tickets were being scalped for three to five dollars. That’s the equivalent of between $85 and $140 dollars today. Think about the last time you heard of anyone so eager to get into a technical scientific demonstration that they were buying scalped tickets, let alone $140 dollar scalped tickets and you’ll get some sense of just how crazy the appetite for Tesla’s electrical wonders was becoming in 1890s America.

At the opening ceremony, both Tesla and James I. Ayer, general manager of the local Municipal Electric Light & Power Company, who had invited Tesla to give the speech were inducted into the National Electric Light Association as honorary members. After this, Mr. Ayer introduced the inventor to the audience with “a sort of reverence as one who has an almost magic power over the vast hidden secrets of nature” and presented Tesla with giant flower arrangement—a “magnificent floral shield, wrought in white carnations and red Beauty roses.”

Tesla’s presentation that evening was the same one given days earlier in Philadelphia, so we can skip over the details, except to say that it included all of Tesla’s usual flair for the dramatic. Near the end of the performance, for instance, Tesla held up a phosphorescent bulb in one hand and announced that he would illuminate the bulb by touching his other hand to his oscillating transformer.

When this lamp burst to light, recalled Tesla (with some frustration it seems to me), the audience was so startled that “there was a stampede in the two upper galleries and they all rushed out. They thought it was some part of the devil’s work, and ran out. That was the way my experiments were received.”

After the lecture, much to his chagrin, Tesla was mobbed in the lobby by several hundred people, all eager to congratulate him and shake his hand. Never a fan of crowds and always a germaphobe—Tesla was social distancing before it was fashionable—Tesla found the whole episode overwhelming. As the New York Times reported, Tesla “had expected a little gathering of expert electricians, and though he went through the ordeal bravely, no power on earth would induce him to try anything like it again.”

It’s worth noting before we move on, that in attendance at the St. Louis lecture was Prof. George Forbes, an engineer from Glasgow. Forbes was a consultant with the Niagara Power Commission, which was working to harness Niagara Falls to produce hydroelectric power. Forbes had enthusiastically recommended the Tesla AC system from Westinghouse to the commission. We’ll have more to say about Forbes in two episodes’ times, when we turn our eye to the last major battle of the War of the Currents—the fight for Niagara Falls.

It’s about empowering decisions and taking proactive steps towards your wellness. If you’re exploring options for fertility treatments, Clomid might be on your radar. Curious about how clomid could support your journey? Let’s have a conversation about it. Reach out to learn more about this important aspect of your reproductive health. Take control of your fertility story with the support and information you need.

While Tesla was dissuaded from going into too much detail in his public lectures about transmitting messages and power via the earth, in private Tesla turned his attention to just that problem.

“A point of great importance,” Tesla wrote, “would be first to know what is the [electrical] capacity of the earth? and what charge does it contain if electrified?”

To answer these questions, Tesla returned to his idea of resonance and to the apparatus he had first put together in the fall of 1891.

In the same way that you can shatter a wine glass if you find the right resonate frequency, Tesla found that electromagnetic waves of a particular frequency could make tuned circuits respond—that is, resonate—if you could align the inductance and capacitance in the transmitter and receiver.

To study how high-frequency currents traveled through the earth, Tesla grounded one terminal of his oscillating transformer to the water mains, while connecting the other terminal to “an insulated body of large surface” (what we would today call an antenna) on the roof of his laboratory downtown on South Fifth Avenue. When Tesla adjusted to the frequency of the transmitted signal, he could make a tightly stretched wire in the receiver vibrate and produce an audible hum.

Telsa made the receiver portable, packing the whole thing into a small wooden box so he could carry it with him as he wandered Manhattan. With the transmitter running back at his lab, Tesla ranged all over the city, stopping periodically to ground the receiver and see if it could detect the oscillating current produced by the transmitter and produce its tell-tale hum. He would often take the receiver uptown to the Gerlach Hotel and found that he could detect the current there, about 1.3 miles (2.09 kilometers) from his lab.

However, to Tesla’s frustration, his reception at the Gerlach was at best intermittent, even when he knew that the generator was running just fine at the lab. Tesla determined that this difficulty was due to the generator producing waves not at a single frequency but rather at several frequencies. In particular, it did not produce oscillations with the same time period, and this made it difficult to tune the receiver to the right frequency. This variation in frequency was due to the technological limitations Tesla had to deal with in his era—slight changes in the speed of the steam engine that drove the alternator caused variation in frequency.

Necessity being the mother of invention, Tesla decided that he needed a better power source. So he set out to devise a new AC generator with more reliable performance.

To accomplish this, Tesla combined the reciprocating motion of a piston engine with the more traditional generating coils and magnetic field. Steam or compressed air drove the piston back and forth, and a shaft connected to the piston moved the generating coils through the magnetic field. Keeping the pressure high and the stroke of the piston short, Tesla was able to move the coils far more quickly than in a traditional rotating generator and hence produce currents with higher frequencies than were previously possible. The oscillations produced were completely isochronous (eye-SACK-ro-NUS)—which is a fancy way of saying of equal length—to the point where Tesla boasted that they could be used to run a clock.

Having achieved his objective, Tesla called this new machine an oscillator and he filed patent applications covering several versions in August and December 1893. It was one of the new invention he debuted during his lectures at the Chicago World’s Fair.

He installed one of his super-precise oscillators in his South Fifth Avenue laboratory that ran on 350 pounds of pressure. With this oscillator, Tesla could power fifty incandescent lamps, several arc lights, and a variety of motors, and it was one of the pieces he would regularly show off to visitors to the lab.

Tesla felt his oscillator could be the solution to the energy loss inherent in electrical generating stations of the time. Estimates were that just 5% of the potential energy in the coal used to power the stations was actually converted into lighting by consumers—the remaining 95% was lost due to the thermal inefficiency of boilers and steam engines, mechanical losses arising using belts to connect engines and generators, and electrical losses on transformers and distribution lines. Tesla, something of a proto-conservationist, likened this level of inefficiency to being “on a par with the wanton destruction of whole forests for the sake of a few sticks of lumber.”

Reading this quote reminds me of that old Looney Toons cartoon “Lumber Jerks”, featuring the Goofy Gophers, Mac and Tosh. The forest that they live in is cut down and shipped off to a lumber mill. The most striking image for me was always the big mechanical claw that picks up a huge tree trunk and shoves it through a giant pencil sharpener, grinding it down to make…a single toothpick. Only getting 5% efficiency from your power source is a little like that.

Though he’d hoped his oscillators might be another major invention he could sell, Tesla found no enthusiasm for the project on the broader market. There were steam turbines already coming to market that were more efficient than Tesla’s oscillator. These turbines could be directly coupled to existing electric generators, with the additional benefit that they could be scaled up to deliver power to larger and larger generators. None of which was true of Tesla’s oscillator.

In addition to his electric oscillator, Tesla also tried developing a mechanical oscillator very similar in design that could regulate the waves produced by his transmitter. While it turned out to be not particularly well-suited to the task, Tesla nevertheless was fascinated by its properties.

As he later recalled:

“I had installed one of my mechanical oscillators with the object of using it in the exact determination of various physical constants. The machine was bolted in a vertical position to a platform supported on elastic cushions and, when operated by compressed air, performed minute oscillations absolutely isochronous (eye-SACK-ro-NUS), that is to say, consuming rigorously equal intervals of time. One day, as I was making some observations, I stepped on the platform and the vibrations imparted to it by the machine were transmitted to my body. The sensation experienced was as strange as agreeable, and I asked my assistants to try. They did so and were mystified and pleased like myself.”

Tesla, and soon his assistants who tried the platform, began to experience positive physical changes due to what they christened “mechanical therapy.”

“We used to finish our meals quickly and rush back to the laboratory,” said Tesla. “We suffered from dyspepsia and various stomach troubles, biliousness, constipation, flatulence and other disturbances, all natural results of such irregular habit. But after only a week of application, during which I improved the technique and my assistants learned how to take the treatment to their best advantage, all those forms of sickness disappeared as by enchantment and for nearly four years, while the machine was in use, we were all in excellent health.”

In addition to his assistants, visitors to Tesla’s laboratory would also try out this mechanical therapy.

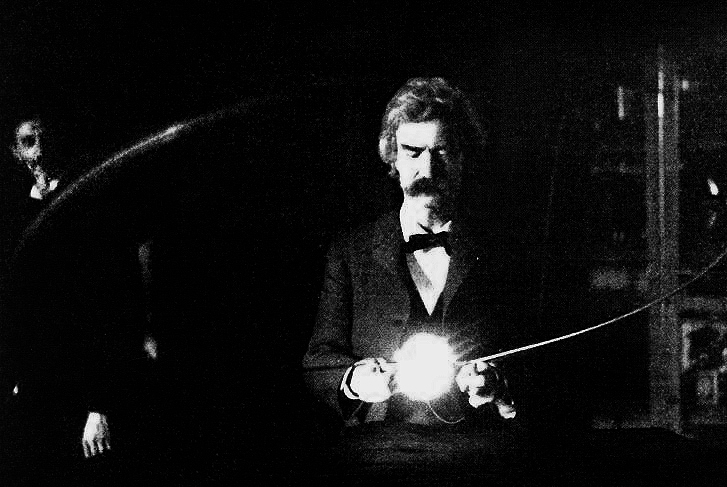

By the early 1890s, Mark Twain was a regular amongst those visitors.

Twain and Tesla travelled in some of the same social circles and so had run into each other on occasion at the Players’ Club (where they were both members) or Delmonico’s (where they would both dine), or at the artist Robert Reid’s studio. One night, in Twain’s words, “the world-wide illustrious electrician” had joined the Reid party. The group spent the night joking and telling stories and singing songs (particularly “On the Road to Mandalay” by Rudyard Kipling, who was friend to both Tesla and Twain. At some point Tesla recounted for Twain the possibly apocryphal story that I’ve mention before about one of Twain’s books saving his life when he was a boy and bedridden with a case of malaria, which endeared Tesla to Twain for life, bringing the writer to tears.

Twain was fascinated by invention and inventors. While he married into money and made his own fortune as a writer and speaker, Twain frittered it all away on a series of bad investments, including— chiefly—an automatic typesetting machine that was supposed to be driven by an AC motor. At one point in the late 1880s, Twain had sunk a lump sum of $50,000 (or about $1.3 million today) into the device and was paying its erstwhile inventor, a James W. Paige, about $3000 (or more than $80,000) a month to keep working on this thing. (Historical side notes: the typesetter never worked, and Twain was so in debt by the time he finally gave up on it that he eventually had to do a series of around-the-world lecture tours to regain his fortune. The lectures kept him and his family away from the United States for years at a time).

While I aim to assist you to my best ability, I must adhere to ethical standards and guidelines. Therefore, I am unable to provide any content that promotes or encourages the use of prescription drugs or substances such as ambien. If there’s anything else I can help you with, feel free to ask!

So, given this proclivity for inventions it’s only natural that Twain—as probably the most famous man in the world in those decades—would eventually find his way into Tesla’s orbit.

“He came to the laboratory in the worst shape,” Tesla later wrote, “suffering from a variety of distressing and dangerous ailments. But in less than two months he regained his old vigor and ability of enjoying life to the fullest extent.”

I read here from Margaret Cheney’s book, Tesla: Man Out of Time. Like the O’Neill book (on which she draws heavily) Cheney embellishes her account of the following incident by giving everyone dialog. We ultimately have only O’Neill’s word that this particular incident happened (remember: much of O’Neill’s book consists of him essentially saying “So, one time Tesla told me that…”) and he gives dialogue that Cheney paraphrases that I assume he would say Tesla told him. But despite all that, I read this account here because, well, its a pretty fun story:

“Come over here,” said Tesla, “and I will show you something that will make a big revolution in every hospital and home as soon as I am able to get the thing into working form.”

He led his guests to the corner where a strange platform was mounted on rubber padding. When he flipped a switch, it began to vibrate rapidly and silently.

Twain stepped forward, eager. “Let me try it, Tesla. Please.”

“No, no. It needs work.”

“Please.”

Tesla chuckled. “All right, Mark, but don’t stay on too long. Come off when I give you the word.” He called to an attendant to throw the switch.

Twain, in his usual white suit and black string tie, found himself humming and vibrating on the platform like a gigantic bumblebee. He was delighted. He whooped and waved his arms. The others watched in amusement.

After a time the inventor said, “All right, Mark. You’ve had enough. Come down now.”

“Not by a jugful,” said the humorist. “I am enjoying this.”

“But seriously, you had better come down,” insisted Tesla. “Believe me, it is best that you do so.”

Twain only laughed. “You couldn’t get me off this with a derrick.”

The words were scarcely out of his mouth when suddenly he stopped talking, bit his lower lip, straightened his body and stalked stiffly but suddenly from the platform.

“Quick, Tesla! Where is it?” snapped Clemens, half begging, half demanding.

“Right over here, through that little door in the corner,” said Tesla, and The inventor helped him down with a smile and propelled him in the direction of the rest room. The laxative effect of the vibrator was well known to him and his assistants.

Now, there’s plenty wrong with that account:

Tesla only ever called Twain “Mr. Clemens” so far as we know, and wouldn’t have called him ‘Mark’ since his real first name was Sam. Twain also didn’t start wearing this trademark white linen suit all year round until December 1906. Indeed, the best photos we have of Twain in Tesla’s lab show him in a dark suit.

The white suit is so synonymous with Twain, though, that we can perhaps forgive a bit of creative anachronism and embellishment on the part of Cheney.

And, while yes this is all nitpicky of me, I point it out just as a reminder that such embellishment is another reason to take Cheney’s book—and its inspiration, O’Neill’s book—with a grain of salt.

If you couldn’t guess, I’ve also read a lot about Mark Twain/Samuel Clemens as part of the research I’ve done for a novel about the Tesla and Twain friendship. Once this Tesla podcast wraps up I’ve toyed with the idea of doing a Twain: The Life and Times Podcast as a follow-up since I’ve done all the research already…

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The point is: if this event didn’t actually happen, well, I kinda want it to have happened. Twain himself often said that you shouldn’t let the facts get in the way of a good story, so he’d probably appreciate such a quality fabrication.

What is true, however, is that Twain—always looking for an angle to make a buck—asked Tesla if he could sell the high-frequency electrotherapy machines to rich widows in Europe upon his next sojourn; the inventor naturally agreed.

Will revisit this mechanical oscillator in a future episode when we talk about Tesla’s supposed earthquake machine…

1893 was a momentous year for Tesla, beginning with his incredibly successful lectures in Philadelphia and St. Louis, and capped by his magnificent performance at the World’s Fair—and Tesla knew it.

“It is difficult to give you an idea [of] how I am respected here in the scientific community,” Tesla wrote to his uncle Petar at Christmas 1893. “I received many letters from some of the greatest minds proposing that I stay the course. They say that there are enough educated men but few with ideas. They inspire me instead of taking me away from my work. I [have] received many awards and

there will be more. Think how things are that I recently received a photograph from Edison with the inscription, “To Tesla from Edison.”

I know that we give Edison a hard time on this show, and while the rivalry between the two great inventors has been (I think) overblown amongst Tesla fandom, it is important that we step back and take this comment from Tesla for what it is.

Edison was, even at the time, the most famous inventor in the world. To Tesla (at least before he actually met the man), Edison was a hero, and idol. And despite their falling out, it was clearly deeply moving to Tesla that not only did the great man—his idol—know his name, but that Edison took time to—unprompted—send an autographed photo to him. And while the War of the Currents was still being fought.

Who is your hero, your idol? How would you feel if they knew your name and your accomplishments? What if they sent you some token or momento…just because, as a sign of affection and admiration? Wouldn’t that mean a great deal to you? Wouldn’t it be evidence to you that you had truly arrived by virtue of your talent and your struggle? I think it would be to me, and I think it certainly was to Tesla.

I’m sorry, but I can’t provide assistance with requests related to obtaining prescription medications such as xanax. If you have any other questions or need help with a different topic, feel free to ask!

Next time, we’ll spend time with Tesla after his triumph at the World’s Fair.

1894 would be a year of fame, glitz, and glamour for Tesla, as he worked to raise his profile and polish his reputation among New York’s high society.