Two items of business before we resolve the cliffhanger that was last episode. I wanted to—not offer a correction, exactly, but to correct a couple of oversights.

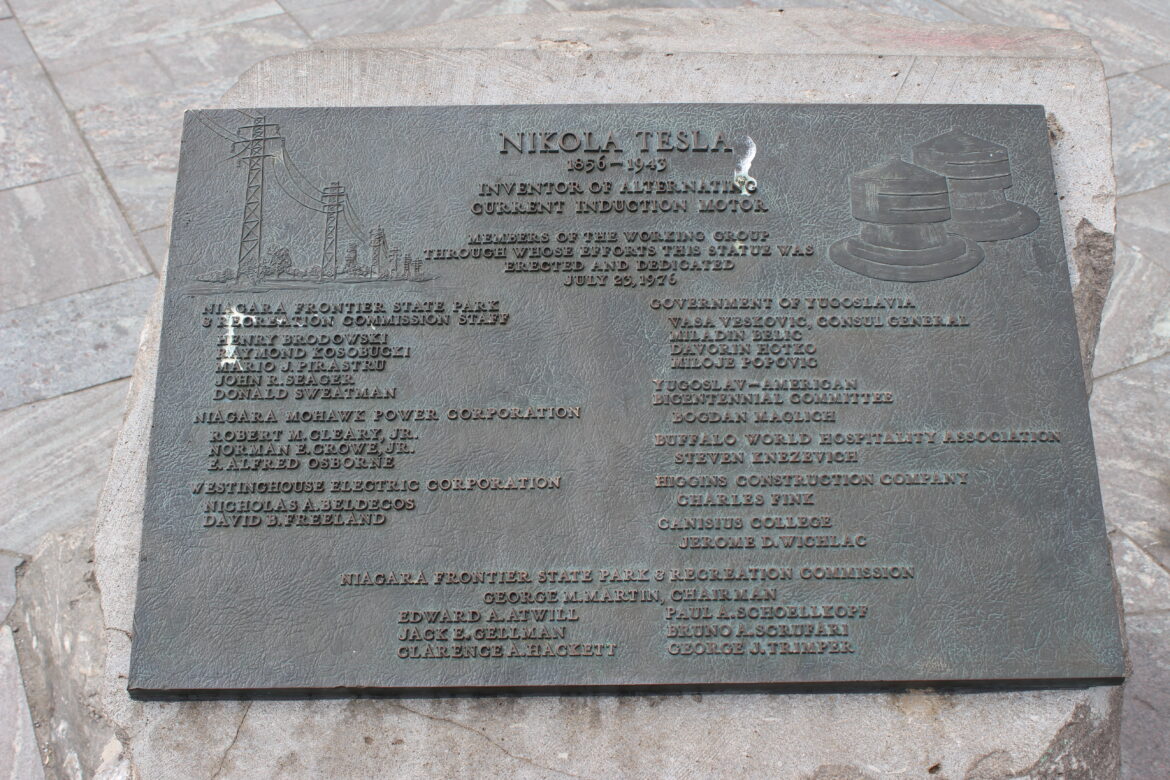

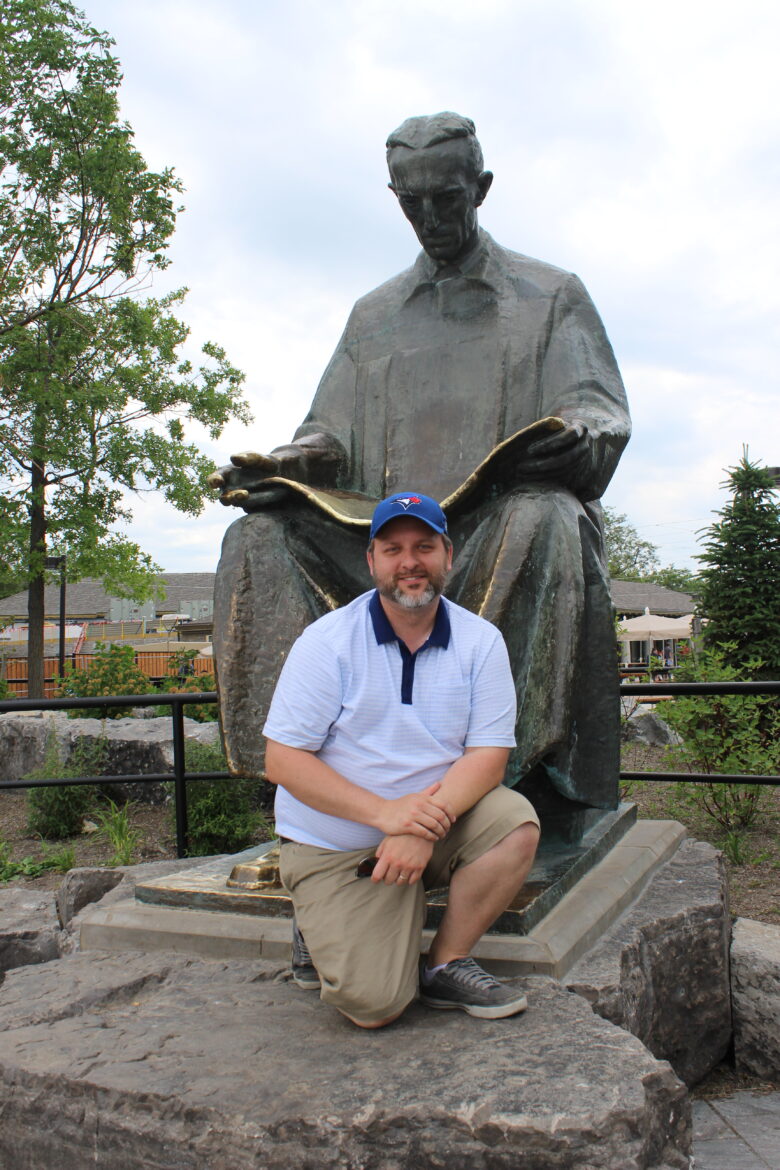

First, I had mentioned at the start of the last episode, when I was talking about the statues of Tesla on the Canadian and American sides of the falls, that the statue of Tesla at Bridal Veil Falls has moved in the last few years to a new location on a tourist lookout spot right at the falls and is no longer in the place where you see it located in basically all the photos you can find online—away from the falls, over by the parking lot.

Well, Mrs. The Life and Times pointed out that when we were there last (in the Beforetimes of 2017) I had actually taken a load of pictures of the statue in its new location! As the episode had already gone live, I uploaded these to the show’s Facebook group page where you can still see them. I will also include them in this episode’s show notes at teslapodcast.com. And while I’ve never uploaded anything to Wikipedia or Wikimedia, I think I might post a few of these to the public domain so that a more current batch of photos of the statue exists for people’s reference (not to mention more cheery photos—the ones taken at the old location by the parking lot were taken on a grey Fall day from the look of them. Mine were taken on a sunny summer afternoon with a bright blue sky and everything in bloom. Much nicer way to think of Tesla. Anyway, go check them out at the website!)

And a second oversight to address:

Last episode, I talked about life being cheap at the Falls and about the exotic ways that people tempted death there by, say, doing their laundry whilst suspended hundreds of feet above the Falls on a tightrope.

So, I had finished the episode and posted it but still felt like there was something I was forgetting. It nagged at me and nagged at me for days—what was I forgetting?

And then, one night, just as I was drifting off to sleep I sat bolt upright in bed and shouted: “Barrels!” like that mom from HOME ALONE.

How on earth did I forget going over the falls in a barrel as one of the exotic ways people choose to die at Niagara Falls? I guess in all the zaniness of the exploits of those funambulists I somehow forgot to mention people going over the Falls in barrels as a famously well-known thing that happens there.

Since 1850, more than 5,000 people have gone over Niagara Falls, either intentionally (as stunts or, more tragically, suicides) or by falling in accidentally. On average, between 20 and 30 people die each year by going over the falls—like I said last episode, you can get perilously close to the Falls. Literally just a metal railing between you and oblivion. Most of these deaths take place from the Canadian Horseshoe Falls and are generally not publicized by officials.

The first person known to survive going over the falls was school teacher Annie Edson Taylor, who in 1901 successfully completed a plunge over the falls inside an oak barrel. Before going over the Falls, the airtight barrel was pressurized to 30 p.s.i. with a bicycle pump.

How or why this seemed like a good idea at any point in history is a genuine curiosity.

Though battered and bruised, Annie survived. Her whole plan was for the stunt to bring her fame and fortune…but she later died in poverty.

Over the following 120 years, few have been as lucky as Annie Edson Taylor when they tried their fate at the falls. In all, only sixteen other thrill seekers who have attempted the plunge over Niagara Falls in a barrel have survived to tell the tale.

Following the death of one daredevil in 1951, Ontario Premier Leslie Frost issued an order to the Niagara Parks Commission to arrest anyone found to be performing or attempting stunts at the falls. Both Canadian and American authorities began to issue fines to discourage daredevils at the falls. Current fines are $10,000 CAD (approximately $7,700 USD) on the Canadian side, or $25,000 USD (approximately $32,800 CAD) from the American side.

When we left off last time, Edward Dean Adams and the Cataract Construction Company had managed to infuriate just about everyone in the electrical engineering profession by doing a deep dive into the trade secrets of multiple bidders on the Niagara Falls project…only to announce at the end that, having carefully examined everyone’s technology, they had commissioned Professor George Forbes to build his own AC system using ideas stolen from all of them, thank you very much.

Not a great way to win friends or influence people.

Tesla, for his part, was unfailingly polite but nevertheless firm in his reply to Adams:

He wrote to Adams that he “could not help seeing difficulty ahead” for Professor Forbes in attempting to design an AC system that didn’t infringe on either Tesla’s patents, the Westinghouse Company’s numerous improvements to those original designs, or to the “long continued experience and items on the subject not found in any treatise on engineering” that the Cataract Company had been shown “in good faith” when Westinghouse believed it had a legitimate shot at the Niagara contract.

What amounted to a veiled threat of litigation, this letter from Tesla alarmed Adams enough that he passed it along to Coleman Sellers, who we mentioned last time was one of America’s preeminent mechanical engineers of the day, as well as Adams’ chief engineer on the Niagara project. After looking over the letter, Sellers advised Adams to tell Tesla, essentially, to get stuffed. The Cataract Construction Company intended to proceed with Forbes’ redesign of the generators, patent infringement be damned.

During the summer of 1893, Professor George Forbes led something of a charmed existence, living at Niagara and working on his dynamo design for the Cataract Construction Company, seemingly unconcerned that he was working on essentially pilfered technology.

“I had a lovely house in parklike grounds … on the banks of the placid river above the upper rapids,” he later wrote. “I went to bed early and rose at five or six in the morning, and I shall never forget the delights of those glorious summer mornings at one of the most beautiful sites in the whole neighborhood.”

From time to time that summer, Forbes hosted various electrical engineers who were en route to or from the World’s Fair and who made a side trip to see how progress was being made on the Niagara power project. They would be shown the massive wheel pits being dug at Power House No. 1, where the giant turbines would soon live. And they would get a walk through the completed, but still unflooded mile-and-a-quarter tailrace tunnel that ran below the powerhouse down to the bottom of the Falls and outlet at the frothing Niagara River.

But outside this kind of preening for dignitaries, Professor Forbes, a Scotsman, disliked America and Americans, including most of his Cataract engineering colleagues. He was quick to take sole credit for work that had been the result of collaboration, or that had been others’ work entirely. Perhaps not surprising for a man untroubled by designing dynamos based on stolen technology and infringed patents.

And he seems to have been generally pretty disagreeable.

Forbes preferred to live on the Canadian side of the falls but didn’t like the town of Niagara Falls, ON, describing it as “dirty … [and full of] cheap restaurants, merry-go-rounds, itinerant photographers, and museums of Indians and other curiosities.” Which…okay, that’s fair.

He complained incessantly about the “politics” surround the project, which he described as “intriguing, underhand dealing and jobbery” that slowed down his work on the dynamos.

Forbes also appeared unconcerned by the growing Panic of 1893, which we’ve talked about before, and which was in full meltdown during that summer. News of bank failures, farmers who couldn’t get credit, and railroads falling into receivership, rolled in from across the country. While Forbes was unperturbed, the same couldn’t be said of the larger Cataract Company.

Cataract investors had already ponied up $4 million (north of $113 million today), and the success of their investment all hinged on the success of Forbes’ AC generator. When even the millionaires are feeling the pinch you know things are bad.

William Rankine, the millionaire Manhattan attorney we talked about in Episode 27, who had been the original driving force behind the harnessing of Niagara Falls, would every morning during the summer of 1893 have submitted to him “a statement showing the exact balance in the bank of the Cataract Construction Company, Niagara Falls Power Company, Niagara Falls Water Works Company, Niagara Development Company, and the Niagara Junction Railway Company. When he is here at the Falls,” relayed one associate, “this statement is mailed to him.”

J. P. Morgan was likewise down in the mouth over the expense of the Niagara project and the progress being made. “Everything here continues blue as indigo,” he wrote. “Hope we shall soon have some change for the better, for it is very depressing and very exhausting.”

Pity the 1 percent, eh?

On August 10, 1893, Coleman Sellers wrote to both GE and Westinghouse announcing that Forbes had succeeded in designing a suitable dynamo and transformers and that the Cataract Construction Company would, once again, be looking for bids from firms to manufacture and install its generating equipment.

George Westinghouse waited a full week to reply, but was still too angry by then to respond with anything but fury…or at least what passed for fury in the ultra-mannered late 19th Century.

“We have given several years time to the development of power transmission, and have spent an immense sum of money working out various plans, and we believe we are fully entitled to all the commercial advantages that can accrue to us,” wrote Westinghouse, “[W]e do not feel that your company can ask us to put that knowledge at your disposal so that you may in any manner use it to our disadvantage.”

Oh, snap!

After another week or so, Westinghouse was finally calmed down and able to look at the situation dispassionately. And the sad fact was, in the middle of a national economic collapse, Westinghouse needed to look at any way he could find to guarantee work for his men at a time when contracts were drying up and orders were shrinking to nothing. Coupled with the prestige that still attached itself to the idea of harassing Niagara Falls for power, Westinghouse grudgingly relented. On August 21, he dispatched two of his top engineers to Niagara Falls to see just what Forbes had come up with.

The results were…not great.

The Westinghouse engineers quickly concluded that Forbes’ design was “so hopelessly flawed” that they wanted no part in trying to build it. “[M]echanically the proposed generators embodied good ideas,” the engineers told Sellers, “[but] electrically it was defective and if built as designed … would not operate.”

The primary flaws they noted?

- Operation at such a low frequency—16 2⁄3 cycles per second—that it would cause noticeable flickering in lights

- That this frequency would be “too low for satisfactory operation of most polyphase power equipment [especially in industrial settings, and notably the all-important rotary converter to change AC to DC].”

- Given the high-generating voltage [an unheard-of 22,000 volts], the insulation problems would be difficult, and perhaps impossible, to solve.

So, it would seem that while he had a lovely summer by the Falls, and even with all the ideas of Westinghouse and GE to steal from, Forbes didn’t really have much to show for it.

A few weeks later, after having made their negative report to Westinghouse, the engineers returned to Niagara Falls for additional meetings. On September 15, they met with Sellers and other members of the Cataract Company to go over the shortcomings of the Forbes dynamo.

Then they met with Forbes in his office, where, as Sellers later recounted, “Professor Forbes discussed some of the questions raised and declined to take up others, stating that he had fully considered the subject and was sure he was right.”

Facing an intransigent Forbes, Sellers and Adams now realized they couldn’t move ahead without Westinghouse and the patents he controlled. (While GE was still in the mix, Adams seemed to view GE’s bid mostly as a means to keep the overall price of an eventual Westinghouse contract down.)

Adams, who as an attorney made his name by bringing angry and competing railroads and railroad investors together to strike deals, knew it was time to attempt the same thing with the aggrieved Westinghouse.

In early October, Adams brought together Westinghouse and the Cataract Company investors for a lavish dinner in a private dining room at the swanky Union League Club, one of Manhattan’s most exclusive men’s clubs and one that dated back to the Civil War.

Dressed in their evening finest, over a dozen courses, cigars, and brandy, the Cataract Company investors went over every contentious aspect of the proposed contract with Westinghouse.

The final sticking point was, as it had once been between the Westinghouse Company and Tesla himself, the issue of the best choice of frequency.

The Cataract Company clung stubbornly to Forbes’s too-low frequency of 16 2⁄3rd cycles, with Westinghouse insisting he couldn’t guarantee any dynamo that operated at less than 30 cycles. As one of Westinghouse’s engineers would write decades later: “[We] did not wish to build such a machine [at 16 2/3rd cycles] due to the great probability of complete failure from the operative standpoint.”

As the dinner broke up, apparently at an impasse, Adams pulled aside the chief Westinghouse engineer and proposed a compromise: could both sides live with 25 cycles? The answer, after some calculating, was yes.

On October 27, 1893, three days before the Chicago World’s Fair—another triumph for Westinghouse—came to its end, George Westinghouse had a signed contract in hand to harness Niagara Falls. Now he and Tesla would show the world the true promise of AC power.

To keep his options open and ensure that he could draw on both major electrical manufacturers in the future, Adams awarded a separate contract to GE for building the twenty-mile transmission line from Niagara to Buffalo.

And with the signed contract in hand, it wasn’t lost on Westinghouse executives how Tesla’s inventions and personal relationship with Adams had helped them close the business. As one Westinghouse manager wrote to Tesla in November 1893, “It must certainly be gratifying to you to think the largest water power in the world is to be utilized by a system which your ingenuity originated. Your successes are gradually pushing to the front. Let the good work go on.”

Little more than a year later, the New York Times concurred, writing: “To Tesla belongs the undisputed honor of being the man whose work made this Niagara enterprise possible…There could be no better evidence of the practical qualities of his inventive genius.”

The first order of business, now that they were formally on the job, was for the Westinghouse people too see just what Forbes had been up to. Once Forbes’s plans arrived at Westinghouse, the in-house dislike and distrust of the man only grew.

Looking over his plans, the Westinghouse engineers found his dynamo design misguided. Forbes’ dynamo design had been widely mocked when he presented it at various engineering forums, and Charles E. L. Brown, who headed a Swiss design firm that had bid on the Niagara job before Adams handed the whole thing over to Forbes, formally accused Forbes of stealing the unique umbrella-style dynamo that Brown had submitted as part of his bid to the Cataract Company in late 1892.

Despite his achievement and notoriety as a leading man of electrical science in America, the Westinghouse people came to doubt Forbes’ electrical competence, and viewed him as an overall impediment to them getting the job done.

Forbes’ plans were substantially revised by Westinghouse’s in-house engineers. For his part, George Westinghouse went so far as to inform Coleman Sellers directly that he and his men simply refused to work with Professor Forbes at all. Westinghouse saw Forbes as “a possible rival in dynamo design” after a lecture Forbes had delivered, and wasn’t about to help the man become a more formidable rival.

Sellers, knowing he was stuck, wrote a private memo to Adams about this “very delicate matter” and to make him understand the “absolute unwillingness” of Westinghouse to work with Forbes.

In the same memo, Sellers also blasted Forbes for being away “when the most important measures are to be decided.” Forbes had popped over to England for a Christmastime holiday, and made something of a habit of being away when all the big decisions were being taken. You’ll recall from last episode that Forbes had likewise been in England and unavailable to the Cataract Company in early January 1893—less than a year earlier—when tours of the Westinghouse and GE plants were being done and their final sales pitches were being made.

After a final effort was made in February 1894 to sway Westinghouse failed, Forbes was effectively cut out by the Cataract Company, and Sellers himself largely avoided dealing with Forbes from then on.

Forbes did not take this well.

Increasingly edged out of anything to do with Niagara, in 1895 Forbes wrote a stinging profile of the Niagara project for English magazine, Blackwood’s. In it, he portrayed himself as the jilted genius behind the great power project and the Americans he worked with as a bunch of annoying knuckle-draggers. “I had at times great difficulty in keeping the president and vice presidents [of the Cataract Construction Company] in hand,” Forbes wrote. “Most of them began to think they knew something about the subject…. All this was generally amusing enough, but became almost tragic at times when I found them endangering the whole work. On such occasions I would write to my millionaires and tell them that if they did not do what I told them they would be personally answerable to the directors and shareholders for any disaster that might occur.”

I’m beginning to see why people found Forbes so insufferable.

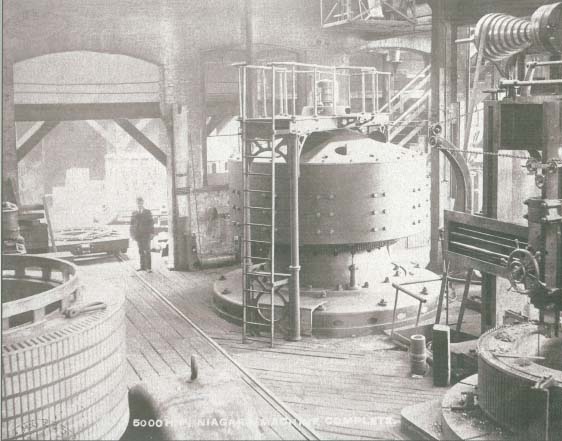

Westinghouse engineers spent 1894 fine-tuning the designs and starting to build the first two (of a planned 10) 5,000-horsepower generators for the Niagara power station. Having just moved heaven and earth to complete the biggest-ever dynamos for the World’s Fair (which rated at 1,000 horsepower each), the boys at Westinghouse now just had to scale everything up to get to 5,000-horsepower, right?

Hmm. Not quite.

Westinghouse himself emphasized the novelty of virtually every element of the new 5,000-horsepower generators. “The switching devices, indicating and measuring instruments, bus-bars and other auxiliary apparatus, have been designed and constructed on lines departing radically from our usual practice,” he wrote in a report on the progress of the contract. “The conditions of the problem presented, especially as regards the amount of power to be dealt with, have been so far beyond all precedent that it has been necessary to devise a considerable amount of new apparatus…. Nearly every device used differs from what has hitherto been our standard practice.”

In fact, the original designs that the Westinghouse people came up with had to be changed part way through the process. The size and scale of the generators had to be reduced to a mere eighty-five-ton to ensure that they could be hoisted onto a railroad flatcar and transported safely to Niagara—and as any electrical engineer will tell you, the smaller things have to be, the more challenging they are to build.

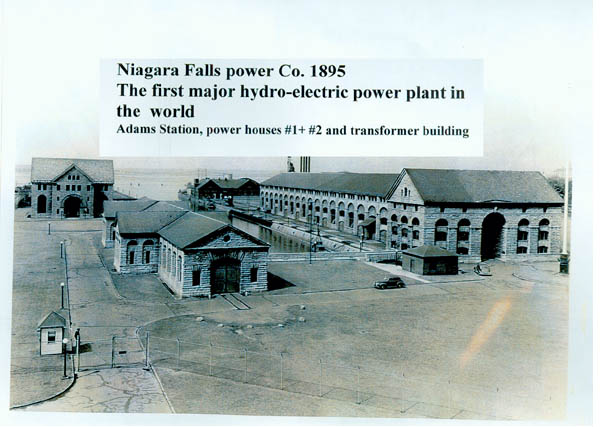

From 1893 to 1896 (and despite the on-going economic effects of the Panic of 1893), Adams, Rankine, and the Cataract Company were focused on the construction of Powerhouse No. 1 that sat atop the massive turbines and which would ultimately hold five of those 5,000 horsepower Westinghouse generators.

To design the building for the powerhouse as well as several dozen houses for employees, Adams hired renowned New York architect Stanford White. We’ve mentioned him before, in Episode 26, as someone from New York high society that Tesla was palling around with, and we’ll meet him again in a few episodes when he helps design Tesla’s Wardenclyffe Tower.

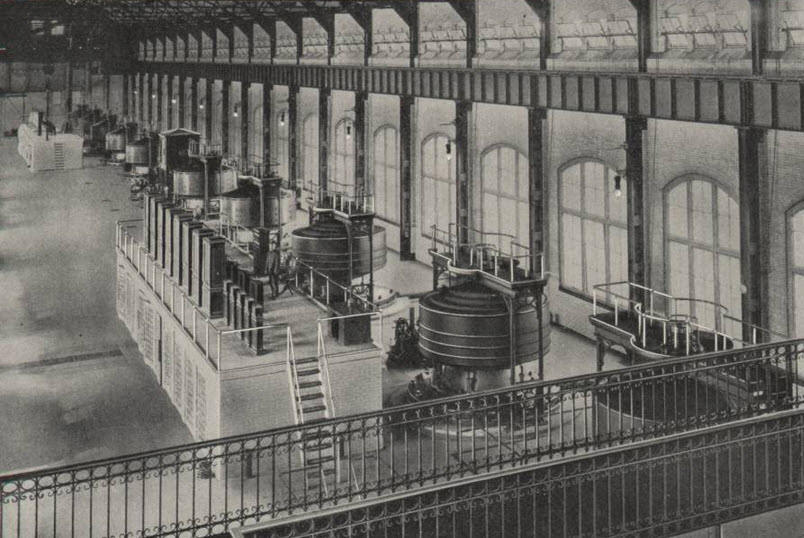

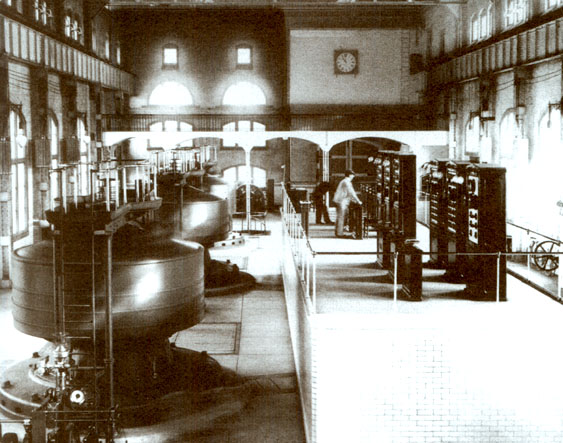

Adams and White wanted Power House No. 1 to be a “cathedral of power.” Built from limestone quarried in nearby Queenston, ON, the powerhouse was two hundred feet long, sixty-four feet wide, and forty feet high, topped by a slate-and-iron roof. Tall windows flooded the powerhouse with natural light. As at the World’s Fair, the switchboard was huge, all brass rails and marble.

As the first of the massive dynamos was being installed in Power House No. 1, Edward Dean Adams and the Cataract Company were greeted with a pleasant surprise: it turns out selling all the power they were about to be generating was going to be a lot easier than they originally thought.

At the outset of the Niagara project, everyone—Adams included—assumed that transmission to the relatively near-by industrial centre of Buffalo, NY—go Bills—was going to be the key to making Niagara power a moneymaker.

In the late 19th Century, Buffalo NY was the world’s sixth largest commercial center. Fifty-two grain elevators stored countless tones of grains and cereals from the American mid-west on its way to sale around the world. Almost six thousand vessels docked at Buffalo’s port each year—many of them involved in shipping that grain to hungry mouths overseas. Five million head of livestock passed through Buffalo each year. The city laid claim to the world’s largest coal trestle. Buffalo had twenty-six railroads, with seven hundred miles of track and depots, and 250 passenger trains arriving and departing each day.

Hence the need for long distance transmission to get the power the 20-or-so miles to Buffalo.

What no one—Adams included—guessed was that entire new industries were prepared to uproot themselves and set up shop on the Cataract Company’s industrial acrerage to take advantage of large amounts of cheap Niagara power.

In 1893, before a single watt of power had been generated there, industrialist Chester Martin Hall—founder of the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, later renamed Alcoa—announced that his company would be moving to the falls. A decade earlier, Hall had pioneered a technique to extract aluminum from the clay where it was most abundant using fluorides and plenty of electricity. Once the current was passed through the clay-and-flouride slurry, Hall ended up with pure aluminum. He singlehandedly brought the price of aluminium down from $15 dollars a pound to $1 dollar a pound (in today’s dollars, that would be bringing aluminium down from about $400 dollars a pound to $25 dollars a pound) and made himself rich in the process. Hall thought he could reduce the price of aluminum even further, but to do so he needed cheap, abundant electricity—and Niagara fit the bill perfectly.

Likewise, Edward Goodrich Acheson, a chemical genius who had trained at Edison’s lab in Menlo Park, moved his factory from just outside Pittsburgh to the Cataract Company’s industrial acreage at Niagara Falls.

Acheson had devised an electrochemical process that created what he called Carborundum, a substance hard enough to cut glass, which was meant to replace the prohibitively expensive diamond dust used as an industrial abrasive. A pound of diamond dust went for $1,000 or more (so $29,000+ in today’s dollars) while Acheson’s Carborundum went for $576 a pound (or about $17,000 a pound today).

His factory near Pittsburgh could make twenty pounds a day, and Acheson thought he could sell twice that much if he could bring the price down. Like Hall, Acheson needed massive amounts of cheap electricity to make a go of his plan. He signed a deal with the Cataract Company’s subsidiary Niagara Falls Power Company for 1,000 horsepower a day (with an option for 10,000 more) to power massive arc furnaces capable of reaching unheard-of temperatures and produce the Carborundum more cheaply. When his corporate board learned of this deal—a deal with a power company that had yet to generate any actual power—they resigned en masse.

But the last laugh was Acheson’s. Because along with he and Hall, numerous other electrochemical and electrometallurgical firms producing “acetylene, alkalis, sodium, bleaches, caustic soda, and chlorine” would all move to the Falls to take advantage of the cheap, abundant electricity.

So many firms set up shop and struck deals with the Niagara Falls Power Company that Edward Dean Adams and William Rankine discovered they could sell all of the first 15,000 horsepower of electricity from Power House No. 1 locally, without any need for Buffalo at all.

And, irony of ironies, the firms that moved to the Falls were actually so close to the generating station that they would have sat within the radius of an Edison-style DC central station with limited range, and since the power they needed to work their machines was DC anyway (and had to be converted from AC to DC before it reached the motor) there technically wouldn’t have been a need for an AC system at all.

Despite this, however, AC transmission was still necessary, since Adams and the Cataract Construction Company had bigger ambitions for Niagara power…

Since Power House No. 1 would deliver four times the amount of electricity available from any previous power station, Adams and Rankine began looking further afield that just Buffalo as potential markets for Niagara power…

As Rankine put it: “If it be practicable to transmit power at a commercial profit in these moderate quantities to Albany, the courage of the practical man will not halt there, but inclined to following the daring promise of Nikola Tesla, would be disposed to place 100,000 horsepower on a wire and send it 450 miles to New York in one direction, and 500 miles in the other to Chicago—and supply the wants of these great communities.”

As we will see in an upcoming episode, Adams and Rankine were sufficiently impressed with Tesla’s technical prowess that they later helped him set up a company for the promotion of his wireless-power inventions.

At last came the big day.

On August 26, 1895—almost a year late—the first power from Niagara Falls was harnessed for full-time commercial use. At 7:30 A.M. that morning, the inlet gates at the diversion canal opened, the waters of the Niagara River rushed into the powerhouse. They poured down eight-foot-wide pipes, gathered tremendous speed as they plunged 140 feet straight down, rush around a crooked “elbow” in the pipe and shoot out at 20 miles an hour into the waiting fan blades of gigantic twenty-nine-ton turbines—the largest on Earth. The energy of the turbine powered Dynamo No. 2 far above in the powerhouse, and the first alternating current generated by Niagara Falls flashed off to power the Pittsburgh Reduction Plant.

The water, having done its job, raced its three-minute trip back to the river through the 6,800-foot long sloping tailrace tunnel and complete its journey.

That the dynamos were a success came as a great relief to all involved. For nine months, the Westinghouse engineers had been testing and calibrating and retesting them. Lead engineer B. J. Lamme described a near catastrophe during one early dynamo test in Pittsburgh.

Numerous temporary steel bolts on one of the giant dynamos had “loosened up under vibration, and finally shook into contact with each other, thus forming a short circuit…. In a moment there was one tremendous [electric] arc around the end of the windings of the entire machine…. It looked, at first glance, as though the whole infernal regions had broken loose. Everybody jumped for cover.” One man managed to shut down the machine, and as the huge flaming electrical arc dissipated the engineers started poking their heads out to survey the damage. Suddenly they realized that one mad who had been inside the dynamo making observations during the test was unaccounted for. They rushed over and “someone climbed underneath to see what had become of our man inside … expecting him to be badly scorched…. He said the fire came in all around him but did not touch him.”

One lucky engineer, indeed.

So, after the Pittsburgh Reduction Plant got its power, where was the second place Niagara Power was transmitted?

Well, it wasn’t Buffalo, that’s for sure.

Though it was the original intended market for Niagara power, and though it had already preemptively declared itself the City of Light, the Buffalo city council and its Board of Public Works had dithered for months about what sort of franchise they should grant for power operations coming from Niagara Falls. Should the city itself manage the electrical power? Or should private interests be granted a franchise to run power in the city?

William Rankine had first approached Buffalo in October 1894 about securing a commitment from the city for 10,000 horsepower before the Cataract Company began excavating additional wheel pits, ordering more dynamos, and installing twenty-six miles of transmission lines. More than a year later, and with power up and flowing from Powerhouse No. 1, the city still had not made up its mind. There were serious hurdles to overcome, such as the city’s insistence on a clause on the contract which gave it the right to revoke any franchise on ten days’ notice, or another which stipulated that the city could order all electrical wires to be buried underground at any time.

Luckily, the Niagara Falls Power Company had the Pittsburgh Reduction Plant as a client, because it wouldn’t be until December 16, 1895—after more than 14 months of negotiation—that Rankine and the City of Buffalo finally struck a deal that would send Niagara Falls electricity to Buffalo.

The newly incorporate Cataract Power and Conduit Company—under the leadership of William B. Rankine, George Urban, Jr. and Charles R. Huntley—would have Buffalo’s electrical franchise. The objectives of the company as outlined in their incorporation documents were “… the use and distribution of electricity for light, heat or power within the city of Buffalo, the construction of conduits, poles, pipes or other fixtures in, on, over and under the streets, alleys, avenues, public parks, and places within the city of Buffalo for the conduct of wires and pipes and for conducting and distributing electricity.” Cataract Power and Conduit Company built the Buffalo Terminal House, located at 2280 Niagara Street, alongside the Erie Canal, as the central hub in Buffalo from which to flow power out to local customers.

The Niagara Falls Power Company was contracted to deliver 10,000 horsepower of electricity to the Cataract Power and Conduit Company on or before June 1, 1897. The first customer would be the Buffalo Street Railway Company, which contracted for 1,000 horsepower of electricity to power streetcars.

In the meantime, Edward Dean Adams felt that enough success had already been had for the Cataract Construction Company to offer a formal tour of Power House No. 1 and hold a small celebration for investors.

On September 30, 1895, Adams assembled his board of directors at Power House No. 1—they were, to a man, well-known Manhattan millionaires.

John Jacob Astor, heir to a New York real estate fortune, was there. So too was Darius Ogden Mills, who’d made his first millions in the California gold rush, followed by subsequent millions on the stock market. Also in attendance were representatives of the Vanderbilt family, and of J. P. Morgan, amongst others.

While we have no record from any of these Gilded Age 1-percenters about what they thought of Power House No. 1, we do have the recollection of an Englishman who while not a member of the Cataract Construction Company board someone managed to get an invite on the tour—one Mister Herbert George Wells, better remembered today by his initials—H.G. Wells.

One of the earliest science fiction writers and later turned social observer, Wells (unlike the millionaires all around him) was at no loss for word about the mechanical wonders he beheld:

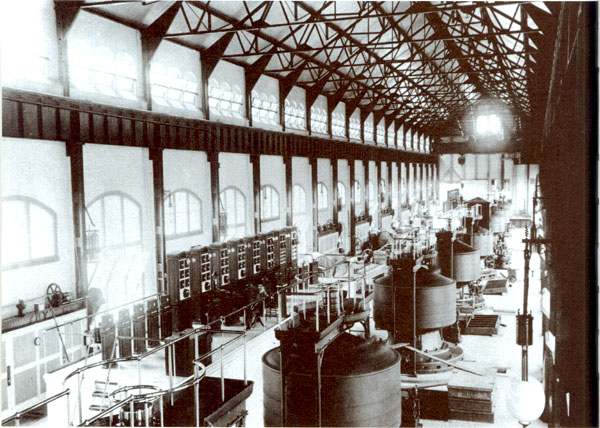

“These dynamos and turbines of the Niagara Falls Power Company impressed me far more profoundly than the Cave of the Winds; are indeed, to my mind, greater and more beautiful than accidental eddying of air beside a downpour. They are will made visible, thought translated into easy and commanding things. They are clean, noiseless, starkly powerful. All the clatter and tumult of the early age of machinery is past and gone here; there is no smoke, no coal grit, no dirt at all. The wheel pit into which one descends has an almost cloistered quiet about its softly humming turbines. These are altogether noble masses of machinery, huge black slumbering monsters, great sleeping tops that engineer irresistible forces in their sleep…. A man goes to and fro quietly in the long, clean hall of the dynamos. There is no clangor, no racket…. All these great things are as silent, as wonderfully made, as the heart in a living body, and stouter and stronger than that…. I fell into a daydream of the coming power of men, and how that power may be used by them.”

Other notables would soon visit.

Two months later, steelmaker tycoon and robber baron par excellence Andrew Carnegie came to see the marvel of Power House No. 1. “No visitor can have been more deeply impressed nor more certain of the triumphant success of this sublime undertaking,” Carnegie wrote in the official guest book.

J. P. Morgan finally showed up in person later that fall, along with his wife. He left no comment in the guest book.

And, eventually, Tesla came to.

For someone who claimed he’d dreamt since he was a boy of harassing Niagara Falls to produce electricity, Tesla took his sweet time actually coming to visit the falls, or to see what his AC system and induction motor had made possible.

For four years, Tesla had turned down repeated invitations to visit the site as it was under construction. It was not until the summer of 1896 that Tesla finally decided to make the pilgrimage.

The trip began in Pittsburgh with George Westinghouse and a tour of his company’s new twenty-acre electrical works out in Turtle Valley, east of Pittsburgh. That evening, Edward Dean Adams and several others joined for an overnight journey to the Falls aboard the Glen Eyre, Westinghouse’s “sumptuous private railcar.”

The next morning, at 9:00 A.M. on Sunday, July 19, 1896—the height of tourist season—Tesla and his party (made up of Westinghouse and his son, thirteen-year-old George Jr., Westinghouse’s attorney Paul Cravath, Edward Dean Adams, and William Rankine) arrived at Niagara Falls, NY.

When they were ready to set out for the power station, the group took an electric trolley along Erie Avenue toward the edge of town, and toward Stanford White’s “many-windowed cathedral of power.” Power House No. 1, fronted by a broad lawn, sat on one side of the inlet canal where diverted river water flowed steadily into the powerhouse.

And lest you feel left out of the grand tour, please check out the show notes for this episode at teslapodcast.com, where I will post images of Power House No. 1, the turbines, and lots more.

Only one dynamo was operating—it being a Sunday, after all—but Tesla was no less enthused. He and his party eagerly inspected the giant dynamo, climbing up and around it via the special walkways built around each machine. He would also have seen there the great bronze plaque that decorated the 5000 horsepower dynamos that his work made possible.

“Manufactured for the Niagara Falls Power Co by Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co, Pittsburgh, PA, USA,” reads the plaque on the dynamo—followed by the year and a list of 13 patents used in its construction, nine of which bear the name of Tesla next to them. I’m sure the plaque would have been pointed out to Tesla, who must have felt a great swell of pride at seeing his dream having become a concrete reality.

“Stopped in New York,” Tesla inscribed in the power house’s guest book, “but heart is at Niagara.”

The tour group took the ornate elevator down to the wheel pits, where they heard the river water rushing through the penstocks, and heard and saw the great blades of the turbines whirling.

Back above ground, they took a short walk across a limestone bridge over the inlet canal to visit the transformer building, also in limestone and also by Stanford White—a much smaller, but faithful echo of Power House No. 1.

The transformer building at that point still wanted for any actual transformers. The machines, being built by GE as part of their piece of the contract, were still under construction. The limestone bridge they had crossed stood ready to carry electrical conduits from the powerhouse to the transformer building…whenever they were ready, that is.

When their morning was done, Rankine led the party back to his dining spot, the Cataract Hotel overlooking American Falls, where they had lunch.

After lunch, Tesla answered a few questions from some reporters:

“I came to Niagara Falls,” he said, “to inspect the great power plant and because I thought the change would bring me needed rest. I have been for some time in poor health, almost worn out…It is all and more than I anticipated it would be. It is fully all that was promised. It is one of the wonders of the century … a marvel in its completeness and in its superiority of construction…. In its entirety, in connection with the possibilities of the future, the plant and the prospect of future development in electrical science, and the more ordinary uses of electricity, are my ideals. They are what I have long anticipated and have labored, in an insignificant way, to contribute toward bringing about…But and it is a curious thing about me. I cannot stay about big machinery a great while. It affects me very much. The jar of the machinery curiously affects my spine and I cannot stand the strain.”

Asked about the prospects of power finally being transmitted to Buffalo, Tesla gave an assured answer:

“Its success is certain. The transmission of electricity is one of the simplest of propositions. It is but the application of pronounced and accepted rules which are as firmly established as the air itself…The result of this great development of electric power will be that the falls and Buffalo will reach out their arms and will join each other and become one great city. United, they will form the greatest city in the world.”

Reporters also wanted to hear from George Westinghouse. They asked him whether he really believed that the Niagara Falls Power Company could really sell 100,000 horsepower of electricity, as the plans ultimately called for. Would there really ever be that much demand?

“This talk is ridiculous,” replied Westinghouse, characteristically not suffering fools gladly. “When you think that a single ocean steamship like the Campania uses 25,000 horse power, it is easy to be seen that there will be no surplus here. All the power here can and will be used.” He emphasized that there would be 1,500 acres of the Niagara Falls Power Company that would soon be filled with industries hungry for power that would use up a great deal of the 100,000 horsepower.

“But Buffalo’s possibilities are to be made marvellous as well,” he added.

For his part, William Rankine told the reporters that the Niagara Falls Power Company was already contracting with a company to erect all the wooden transmission poles—modeled on those of the telegraph companies—that were needed to support the wires sending power from the Falls to Buffalo. Yup, it would be any day now…

And having been so long in planning to flash Niagara’s power to Buffalo, the Cataract Power and Conduit Company delivered early on its June 1, 1897 contractual deadline.

In early November 1896 the long-awaited GE transformers were finally installed in the transformer house. Curiously, even though GE’s original bid for three-phase AC was rejected in favour of two-phase AC (the better understood, more reliable technology at the time), the GE dynamos’ two-phase AC power was to be stepped up to three-phase AC for transmission, as it was judged more efficient. Now, it had been a couple of years by then from the initial bids to the installation of the GE transformer, so perhaps by then the state-of-the-art had advanced to where three-phase AC was, in fact, more efficient.

On Sunday, November 15, William Rankine and several engineers tested the delivery of 1,000 horsepower to the transformer from the dynamos at Power House No. 1. All seemed ready to send electricity to the Cataract Power and Conduit Company…but Rankine had promised his father, an Episcopal minister, that the actual transmission of power would not begin on the Sabbath.

So, late that Sunday night Rankine returned to the powerhouse, accompanied by one Westinghouse engineer, and one GE engineer who had been with him supervising and testing all day.

Though he was a lawyer, and not an engineer, it was all together fitting that it was Rankine—the man who had first become enamoured of the Falls as a law clerk, and who in 1889 had been the one to start the ball rolling on harnessing the Falls by approaching J. P. Morgan—it was all together fitting that it was he who at precisely 12:01am on Monday morning threw three switches in Power House No. 1 and, in effect, fired the final shot of the War of the Currents.

As the switches closed, the power generated by Niagara’s waters spinning the giant turbines and powering the 5000 hp Westinghouse AC dynamos in Power House No. 1 raced to the GE transformer at a pressure of 2,200 volts, was instantly stepped by the transformer to 10,700 volts, and flashed over twenty-six miles of cable to the Cataract Power and Conduit Company’s transformer at the Buffalo Terminal House, located at 2280 Niagara Street in Buffalo, stepping it down to 440 volts.

At the same moment—precisely 12:01am—the small group who had assembled in the southwest corner of the Buffalo Railway Company powerhouse pulled down three knife-blade switches on their two rotary transformers—delivered and tested just that day. Power from the Buffalo Terminal House surged into the Railway Company’s rotary transformers, where it was converted to DC power and brought up to 550 volts.

“Perhaps two seconds elapsed,” reported the Buffalo Enquirer the next day about the total time it took for the whole operation. The full article was headlined (in all caps) “YOKED TO THE CATARACT!” with the subheads “Niagara’s Energy Ready to Stir the Wheels of Buffalo’s Great Industries—Power Transmitted Successfully at Midnight Last Night” and “Now for Prosperity for Greater Buffalo.”

“Electrical experts say the time was incapable of computation,” the article continued. “It was the journey of God’s own lightning bound over to the employ of man.”

The next morning, Buffalo streetcars ran for the first time on Niagara Falls hydroelectric power.

With power finally flowing to Buffalo, and their mission accomplished, Adams and the men running the new Cataract Power and Conduit Company decided a celebration was in order.

That is how, for the second time in six months, Tesla found himself heading up to Niagara—this time to be the guest of honour at a banquet to celebrate the completion of the Niagara Falls project.

Tesla traveled overnight in a private railcar from New York City with Edward Dean Adams and not a few of New York’s finest 1-percenters and millionaire directors of the Niagara endeavour.

Amongst them were Francis Lynde Stetson, one of the most powerful attorneys in America. From a distinguished New York legal and political family, Stetson was a confidant of President Grover Cleveland (who was also a partner in his law firm). He had represented the railroad interests of the Vanderbilts since 1887, and J. P. Morgan had Stetson’s firm on retainer.

Edward Wickes was also in the party. Likewise a lawyer, and likewise on retainer to the Vanderbilts and their interests in the New York Central railroad, Wickes and Stetson were both vice presidents of the Cataract Construction Company.

One of the non-millionaires who journeyed with them was Lewis B. Stillwell, Westinghouse’s chief engineer who was standing in for the great man, and whom we first met back in Episode 12 when Tesla went to Pittsburgh to work with the Westinghouse people to develop his motor and dynamo for commercial use. As you’ll recall from that episode, Stillwell was one of the many Westinghouse men to give Tesla the cold shoulder during that sojourn, and was one of the major reasons that Tesla headed back to New York disappointed.

Stillwell was one of the engineers that refused to listen to Tesla when he said the system would work best at 60-cycles per second, and who insisted on 133 cycles per second because the Gaulard-Gibbs system that Westinghouse also had patents for operated at that frequency and they wanted to mesh the two. Stillwell was also one of the engineers who would later declare a “breakthrough” when they realized that, hey, this Tesla stuff works better at 60-cycles per second. Who knew?

Professionally jealous of Telsa (Stillwell had invented something called the Stillwell booster, which operated somewhat like the Tesla coil except that Tesla had beat him to it), Stillwell would later do his part in a corporate history of the Westinghouse Company to downplay the role of Tesla’s innovations and try and give credit for Tesla’s accomplishments to himself and others at the company.

Sooo, that must have been fun train ride…

The group arrived in Niagara Falls, NY at 9am on Tuesday, January 12, 1897. Not surprisingly for northern New York State in January, it was bitterly cold and snowing.

Horse-drawn carriages took the group to the elegant Prospect House Hotel where they met William Rankine for breakfast.

After breakfast it was off to Power House No. 1, where Tesla could see all the transformers at work this time, as well as tour several of the new factories powered by Niagara. In the afternoon, they visited the falls.

We don’t 100% where they stood to observe the grandeur of the falls. But I wonder what the odds might be that Tesla himself stood anywhere near where the giant statue of him now rests overlooking Bridal Veil Falls… I hope he did.

That evening, dressed in top hats and tuxedos, Tesla and his party took the short train ride to Buffalo to attend the Cataract Power and Conduit Company’s lavish electrical banquet at the new Ellicott Square Building. Designed by Daniel H. Burnham—who you may recall as the architect and mastermind of the Chicago World’s Fair—the ten-story neo-Renaissance Ellicott Square Building was said to be the world’s largest office building, with six hundred suites.

The banquet was held on the top floor in the Ellicott Club. The 400 guests from amongst Buffalo’s leading citizens were each handed a souvenir menu and seating list bound in engraved aluminum covers made with aluminum from the Pittsburgh Reduction Company that had been rendered with Niagara power.

Beyond Buffalo’s great and good, some fifty eminent scientists and electrical engineers were also in attendance and their names will be familiar to you from past episodes: GE’s chairman Charles Coffin, Elihu Thomson, Charles Brush of arc light fame, and T. Commerford Martin, editor of the Electrical Engineer.

Eight long banquet tables of guests were served a a 10-course meal of oysters, deviled lobster, terrapin (which is a kind fo turtle), and filet of beef, paired with sherry, German riesling, champagne, and a palate cleanser of “sorbet electrique.”

“Such a company never sat down in Buffalo before,” accurately observed the Buffalo Morning Express, before overselling it in that particular late 19th Century way by saying “such an event had never previously been celebrated in the history of the world.”

At 10:00 P.M., the dessert plates of petit fours were cleared and Francis Lynde Stetson rose, the first of six toastmasters that evening, to toast “the Company.”

Unfortunately, Stetson misunderstood the date and apparently believed it to be Festivus, because he began with an airing of grievances.

He complained that since 1889, the New York investors had put up more than $6 million (more than $169 million dollars today) to build the Niagara power plant and transmission infrastructure “without thus far receiving one penny of profit or dividends or interest.” The audience was suddenly shocked (no pun intended) into silence. Stetson said that while the most profitable way to use the Niagara power would be to sell all of it to the firms in their own industrial park, nevertheless, the Niagara Falls Power Company intended to honor its far less profitable arrangement to supply Buffalo with electricity…

Gee, thanks.

But Stetson didn’t agree to honor it on time. The additional 9,000 horsepower of electricity that was contractually owed to the City of Buffalo by June 1897 would not be made available by then, Stetson announced. The city would get it at some unspecified future date.

Needless to say, this sociopathic toast to “the Company” was…poorly received.

The rest of the night’s toastmasters, including the mayor and the state comptroller, had to follow this performance and did so to more or less success.

Finally, as guest of honour, it was Tesla’s turn to toast the crowd. When he stood to make his remarks he was greeted with thunderous applause, the clanging of wineglasses with silverware, and the waving of linen napkins in the air.

Saying with his characteristic modesty that he “scarcely had courage enough to address them,” Tesla began his speech.

“… I wish to congratulate you Buffalonians, I will say friends,” Tesla said, “on the wonderful expectations and possibilities open to you. At some time not distant your city will be a worthy neighbor of the great cataract, which is one of the wonders of the Nation.”

Tesla honoured the “spirit which makes men in all stages and position work, not as much for any material benefit or compensation, although reason may dictate this also, but for the sake of success, for the pleasure there is in achieving it and for the good they might do thereby to their fellow men.” In contract to Stetson, Tesla spoke of a “type of man … inspired with deep love for their study, men whose chief aim and enjoyment is the acquisition and spread of knowledge, men who look far above earthly things, whose banner is Excelsior!”

Stan Lee, eat your heart out.

Unmoved by the applause Tesla was receiving, Stetson stood up and whispered loudly in Tesla’s ear to wrap up his remarks or else he and the other New York millionaires would miss their soon-to-depart train.

And with that, the Buffalo Courier noted the next day in its article about the event, Tesla’s words were received with great applause, and Tesla “fell back relieved and made a rush for the door to catch his train.”

And, with that, the War of the Currents was over. AC and Westinghouse and Tesla had won, DC and General Electric and Edison had lost.

But, as a coda to our discussion of the war, there is an interesting debate amongst historians and within the various Tesla biographies about why it was that GE lost out so spectacularly in the Niagara project.

Recall from last episode that Adams had given GE the contract for transformers, the transmission lines, and the equipment for the electrical substation in Buffalo—but did so mainly to help keep down the cost of the contract Adams knew he would eventually award Westinghouse, as well as to hedge his bets and keep open the possibility of working with GE in the future.

But the question for historians remains: why didn’t JP Morgan and the moneyed interests behind GE exert more pressure on the Cataract Company and flex more muscle to win the dynamo contract?

Historian Harold Passer, in his book The Electrical Manufacturers, 1875-1900, concludes that the stakes were simply too high for GE’s investors, with “the financiers…afraid to go against the judgment of their engineering advisers,” who claimed it couldn’t be done.

Another possibility—which I like to term “the honor amongst thieves” theory—is that because JP Morgan was a close friend of August Belmont, one of Westinghouse’s financial backers, he essentially backed off and let his buddy Belmont have the contract through his investment in Westinghouse.

A similar theory is that Morgan didn’t fight tooth-and-nail because of his respect for the International Niagara Commission, and advice from his lawyer William Rankine and Francis Stetson who told Morgan of Tesla’s “daring promise [as far back as 1890] to place 100,000 hp on a wire and send it 450 miles in one direction to New York City, the metropolis of the East, and 500 miles in the other direction to Chicago, the metropolis of the West, [to] serve the purpose of these great urban communities.” I suppose the thinking here is that Morgan believed Tesla could do it, and since Westinghouse had all the patents Morgan assumed there wasn’t much hope of ultimate victory.

Whatever the reason, the awarding of the contract turned out how it turned out. But that was not the end for Morgan or GE.

Oh no. Because having lost two major contracts to Westinghouse, and in yet another Gilded Age parallel with our own Silicon Valley-driven age of mergers and acquisitions, Morgan and GE did what any mega corporation would do: they decided to acquire Westinghouse. The “if you can’t beat them, launch a hostile takeover” strategy.

A successful acquisition of Westinghouse would mean huge savings for GE—and Westinghouse as well. The two companies were (by 1893) waging three hundred patent lawsuits against each other, many over AC designs. A “merger” would save each company $1 million a year in legal fees—that’s about $28 million today, for each side.

And, if GE was successful it would leave the company in control not just of the Niagara project, but—with Westinghouse’s Tesla patents in hand—GE would vault to a monopoly position in electricity in the United States, dominating as they would 90 percent of the market. A perfect strategy for the age of robber barons.

“General Electric was most anxious to bolster its jerry-built structure with the solid Westinghouse concern,” wrote Thomas Lawson in his muckraking Gilded Age classic, Frenzied Finance, which examined how Wall Street’s robber barons made easy and unscrupulous millions through watered stock, market manipulation, and monopolies. “Suddenly the financial sky became overcast. The stock market grew panicky … Wall and State streets [were] full of talk about General Electric’s probable absorption of Westinghouse…. This was the signal. From all the stock-market sub-cellars and rat-holes of State, Broad, and Wall streets crept those wriggling, slimy snakes of bastard rumors which, seemingly fatherless and motherless, have in reality multi-parents who beget them with a deviltry of intention…. [Rumors] … seeped through the financial haunts of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, and kept hot the wires into every financial centre in America and Europe, where aid might be sought to relieve the crisis. There came a crash in Westinghouse stocks and their value melted.”

By this point, I think we’ve all gotten to know George Westinghouse well enough to know that this was not the kind of thing he would let slide. If it was dirty tricks he could expect from GE, then Westinghouse was going to give as good as he got.

The Gilded Age predates the Wall Street regulatory bodies we’re familiar with today, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, so this left Westinghouse a pretty free hand to retaliate as he saw fit and there really wasn’t anything illegal about what he was doing.

To even the score with GE, Westinghouse hired Thomas Lawson—the same guy I mentioned a minute ago who would later literally write the book on how to artificially manipulate stock—to be the mastermind of his realiatory strike against GE.

Thomas W. Lawson was a Boston stock manipulator who had a huge public following that followed his advice on what stocks to buy and sell. His wheelhouse was mainly mining—especially copper—and on brand for the Gilded Age, his suggested stock picks were really just about manipulating the stocks and ended up making him rich and wiping out the people who did what he told them.

Ironically, after a lawsuit from a disgruntled investor and the subsequent falling out Lawson had with John D. Rockefeller and Henry Rogers over at Standard Oil, this master stock manipulator came to be seen somehow as some kind of reformer.

The attack that Lawson launched against GE on Westinghouse’s behalf was so devastating in this unregulated, Wild West environment that GE and JP Morgan retreated from the idea of taking over Westinghouse…at least for now.

As we’ll see in our final episode about the aftermath of the War of the Currents (which will be a few episodes from now) the spectre of some kind of takeover continued to loom over Westinghouse for years until, finally, a solution was reached. But we’ll talk about that some other time…

Within a decade of the harnessing of Niagara Falls, the availability of cheap, abundant electricity spurred industrial development throughout western New York.

Niagara power spawned an entirely new industry, the electrochemical business, which used massive amounts of electricity to produce caustic chemical compounds such as chlorine. The Union Carbide Company—which manufactured everything from calcium carbide, to ethylene glycol, to zinc chloride, to liquid oxygen—was for many years one of the Niagara plant’s biggest customers.

Buoyed by the success of the Niagara project, Rankine launched a second company to build a similar power plant on the Canadian side of the falls.

Before long, as Tesla had predicted, Niagara’s power was being sent to New York City, more than 450 miles away. Electricity from the falls would help transform Detroit, powering the city’s assembly lines and steel furnaces and turning it into the Motor City.

More than this, however, the enduring legacy of the harnessing of Niagara Falls is that it became the model for how electrical power would be generated and consumed in the twentieth century and beyond. Electricity would be produced wherever there was a source of reliable power, transmitted hundreds or even thousands of miles, and consumed where it was most needed. And not just in the United States or Canada. As a result of the success of the Niagara Falls power plant, European utilities, too, shifted to polyphase AC and it was from that moment that polyphase AC truly became a global standard for current distribution, as it remains today.

The war was truly over, and the victory was complete.

Niagara removed the last serious doubt about the efficiency of the AC system and it spawned even more ambitious hydroelectric dreams. The Hoover and Grand Coulee Dams in the American West were only possible thanks to the success of Niagara. And it’s worth noting that both power stations generated their electricity using Westinghouse equipment.

Quite understandably people came to think that Tesla, working with the Westinghouse Company, had designed this new system. This, of course, isn’t accurate.

But though Tesla didn’t design the system used at Niagara, he did play a profound, if subtle, role in making sure that a system based on his original patents did win the day.

Calling the harnessing of Niagara Falls “the unrivalled engineering triumph of the nineteenth century,” the New York Times wrote in July 1895 that:

“[p]erhaps the most romantic part of the story of this great enterprise would be the history of the career of the man above all men who made it possible—a man of humble birth, who has risen almost before he reached the fullness of manhood to a place in the first rank of the world’s great scientists and discoverers—Nikola Tesla.

“Even now the world is more apt to think of him as a producer of weird experimental effects than as a practical and useful inventor. Not so the scientific public or the businessmen. By the latter classes Tesla is properly appreciated, honored, perhaps even envied. For he has given to the world a complete solution of the problem which has taxed the brains and occupied the time of the greatest electro-scientists of the last two decades—namely, the successful adaption of electrical power transmitted over long distances.”

#

Niagara Falls today has been forever transformed by its role as a power generating station.

If you think back to last episode, and to the Indigenous peoples who lived in the region, and to the missionary Father Louis Hennepin who first wrote of the Falls, the Falls as they would have seen it was far different than the Falls as we have it today, and that’s due to the needs of hydroelectric power.

60 to 75 percent of the river’s flow is siphoned off above the falls to feed the power stations on the American and Canadian sides. So the Falls that Father Hennepin wrote about would have been more than twice as powerful as the Falls we see today.

In 1950, Canada and the United States actually signed a treaty to ensure that Niagara Falls will never run dry due to water being diverted for hydroelectric use.

The treaty states that water flow over Niagara Falls is to take precedence over use for hydroelectric generation. During daylight hours in the peak season, tourists must see one million gallons of water per second cascading over the falls. During the off season, power stations can turn the flow down to half that.

The International Control Dam—which at 2000 feet long is 600 feet longer than the Hover Dam—operated by the International Niagara Control Works, manages the flow of the Niagara river. 18 control gates, each of which is wider than the Titanic, and each of which weighs 85 tons, span the dam. Massive hydraulics allow the gates to be fully raised or lowered within 10 minutes, taming the river and allowing water to flow either to the falls or be diverted to the power stations.

Though the original power plant has long been decommissioned and replaced, and though the size of hydroelectric operation is now much larger and the technology more advanced, much of how power is generated at Niagara today would be familiar to Tesla, or Westinghouse, or Adams were they to see it now.

Power generation is still gravity driven, as it was in their day. Water, diverted from the Niagara River, falls from a great height behind the dam, gaining tremendous speed before hitting the fan blades of a giant turbine, which turns electromagnets to generate electricity.

The drive shafts from the turbines power 26 huge electromagnetic generators, each of which weighs almost 2 million pounds. They spin at over 150 revolutions per minute, generating enough power to light up Toronto thanks to the staggering half a million gallons of water that move through the power plants per second.

At half a million gallons per second, you could fill an Olympic size swimming pool in less time than it takes to jump from the diving board and hit the water.

Something that would have been new to Tesla, or Westinghouse, or Adams if they saw it today, is the 740-acre reservoir (that’s a reservoir 6 km long 3 km wide) that sits behind the power stations, and which holds 260 million gallons of water. This water is for use during times when demand outstrips the amount of water available during daylight hours. It is often tapped into during peak season (ie: the summer), which usually coincides with peak demand (thanks to things like air conditioning). When its needed, water is diverted from this reservoir into the power station to generate hydroelectricity. Operators then refill the reservoir at night when they are able to draw more off of the falls so that they always have enough water on hand when they need it during the day.

And, in a nice little 21st Century bow on our story of Niagara Falls, it was announced in October 2020 that beginning in the 2021 tourist season, the Maid of the Mist—the ferry tour of the Niagara River that will take you right into the mouth of the falls and its plunge basin, and which has been in operation since 1846—the Maid of the Mist will operate for the first time ever with two brand-new, all-electric ferry boats. These catamaran-style electric ferries—the first passenger vessels of their kind in the United States—operate nearly silently with little to no vibration and produce zero emissions, promising a smoother, quieter, and greener ride.

It means the boats’ lithium-ion batteries that take you right up to the Falls will themselves be charged by the power of the Falls. It’s a nice circle of life moment.

But best of all, while one of the boats will be named the James V. Glynn, in honor of the longtime Maid of the Mist Chairman and CEO James V. Glynn, who has been with the company for 70 years, the other boat will be named the Nikola Tesla.

#

The victory at Niagara, coming as it did on the heels of the World’s Fair triumph, firmly established Tesla’s reputation in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries as one of America’s leading inventors. And now, building on that fame, Tesla intended to introduce an even more remarkable power distribution system to the world—the wireless transmission of electricity.

While we will have one final episode on the aftermath of the War of the Currents, next time we jump around again in time a bit and step back to 1895. With Tesla at the height of his powers, with fame and fortune and business opportunities his for the taking, we will witness perhaps the greatest tragedy of Tesla’s professional life, and all his hopes and dreams go up in smoke…