Tesla realizes he’s reached the limits of experiments he can do on wireless transmission from his Manhattan laboratory when he almost lays waste to his entire neighborhood with an earthquake machine.

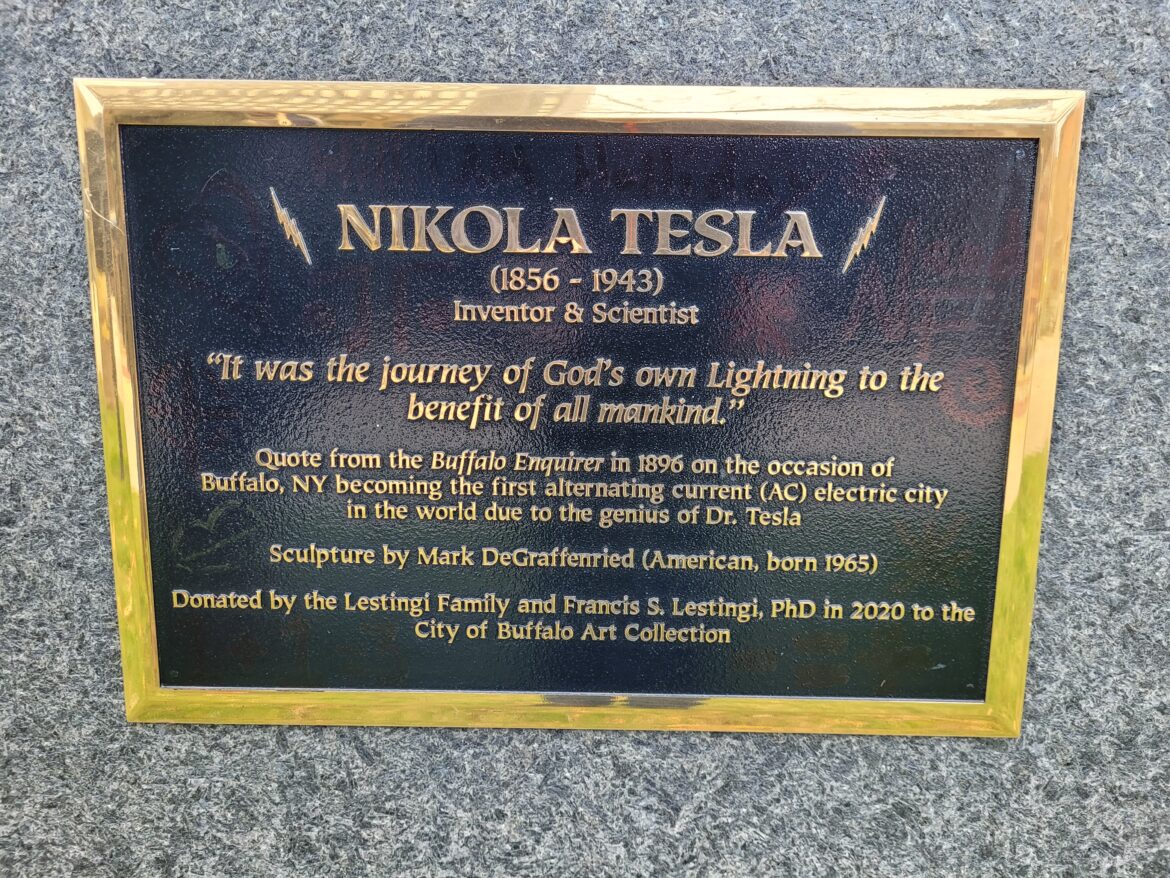

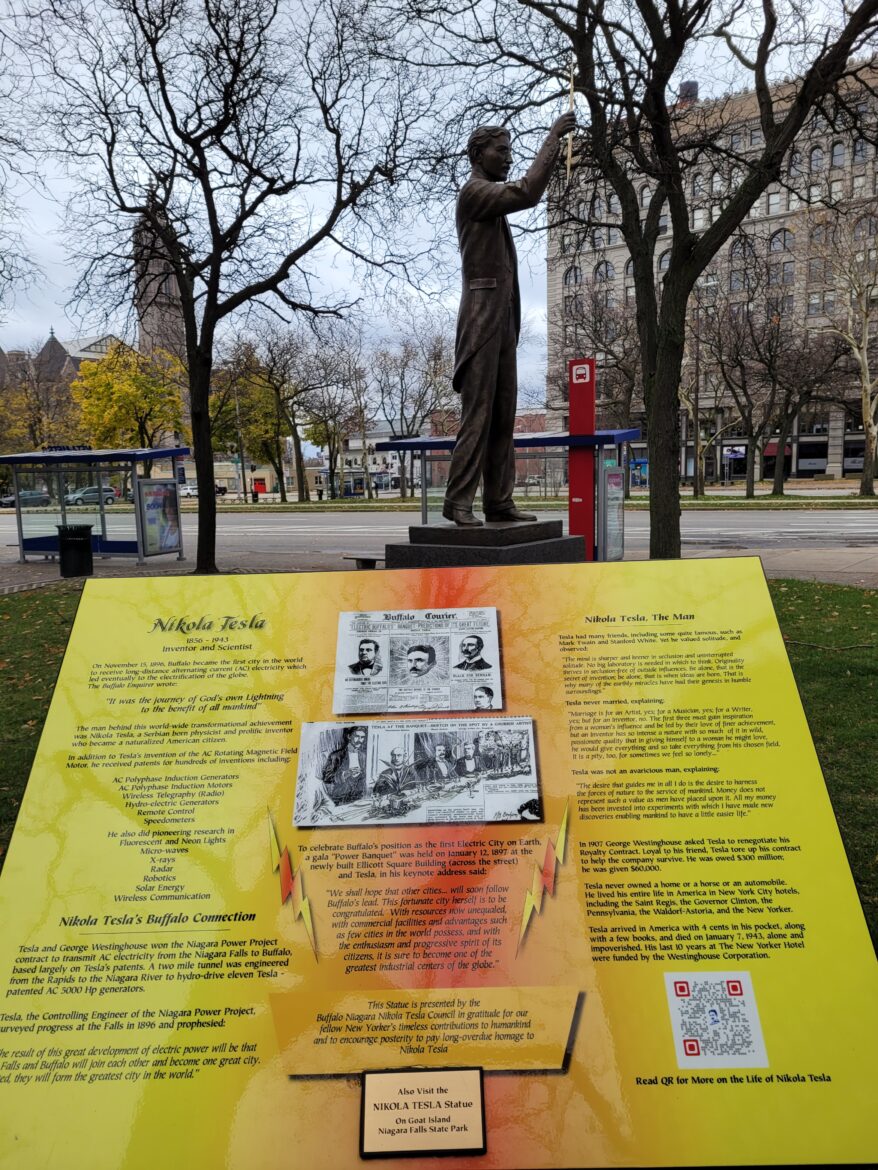

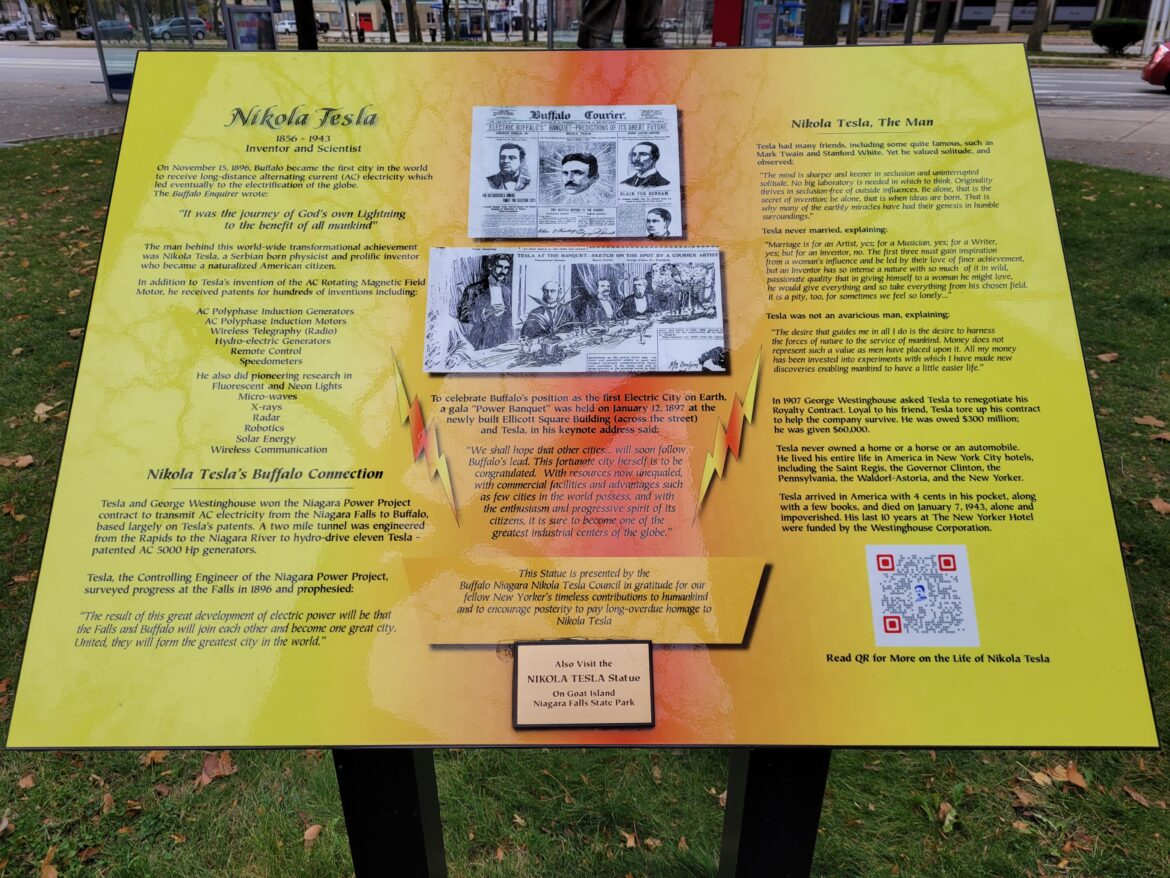

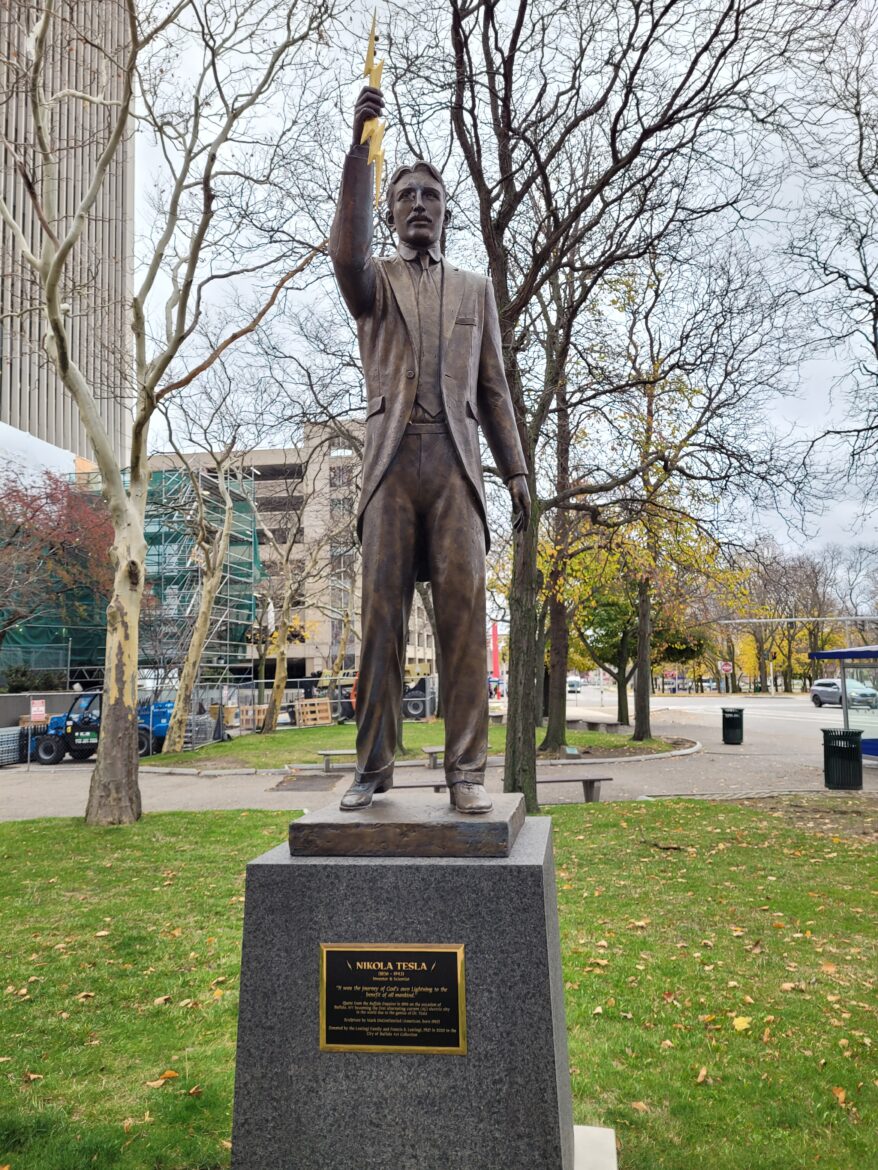

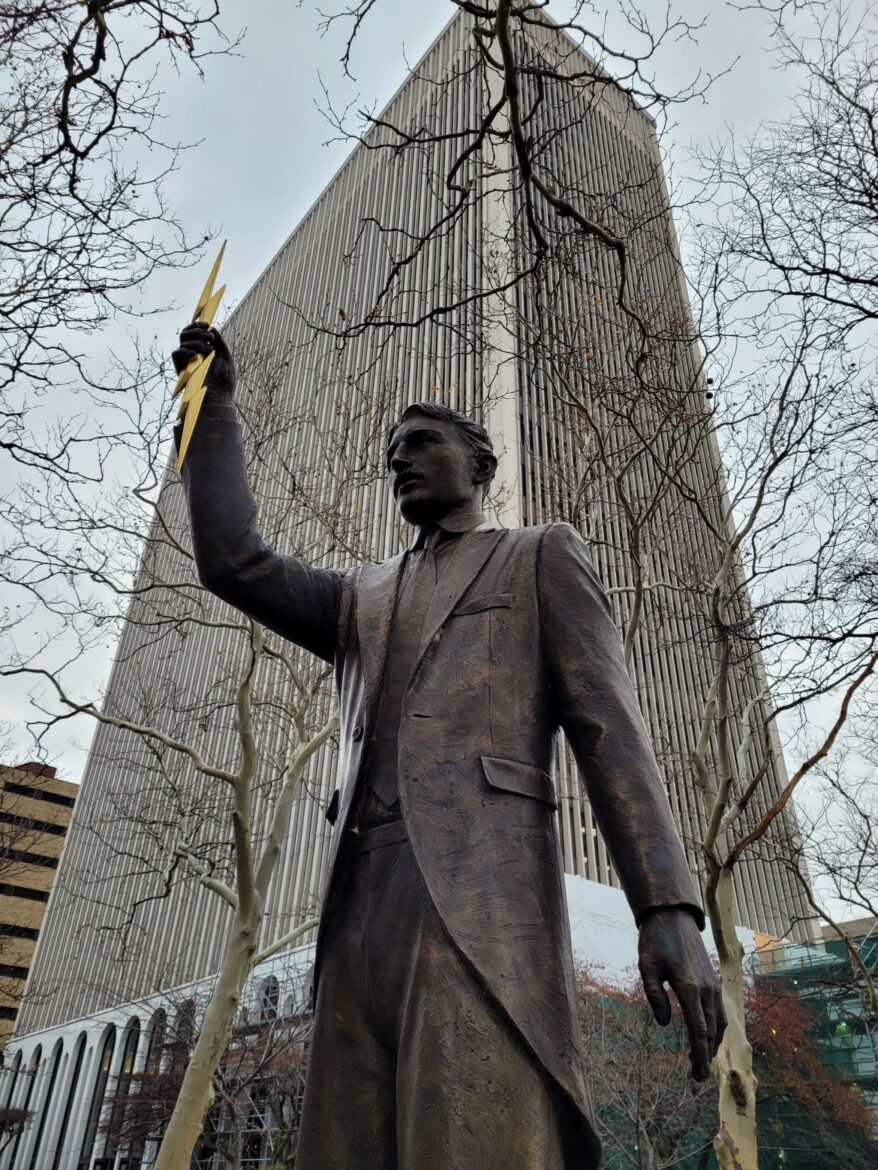

My visit to Nikola Tesla Park in Buffalo, NY!

SHOW NOTES – EPISODE 032

While we talked around the Spanish-American War last episode, we need to take a closer look at the war and how it influenced Tesla and his work now that we’ve arrived in 1898.

You might recall that we first talked about the Spanish-American War way back in Episode 8 on the Gilded Age.

While the war comes smacked dab in the middle of the Gilded Age, its roots go back as far as the 1880s, when imperialists and anti-imperialists in Congress clashed over what role the United States was to play on the world stage.

While the thought of expanding trade opportunities for domestic products fuelled the desire for a strengthened US presence worldwide, the appeal of increasing the territorial advantage of the United States was equally important to imperialists.

Eventually, the imperialists would win the argument — but only after leading the nation into war with Spain in 1898 over the issue of (of all things) Cuban independence.

Revolts against Spanish rule had been occurring in Cuba for years, but in the late 1890s, U.S. public opinion was agitated by anti-Spanish propaganda and calls for war led by newspaper publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst.

You may recall that both Pulitzer and Hearst were pioneers of “yellow journalism”–a type of journalism that presented little or no legitimate well-researched news and instead used eye-catching headlines (including some printed in garish yellow ink–hence the name ‘yellow journalism’) to sell more newspapers. They would engage in exaggerations of news events, scandal-mongering, and sensationalism.

In this case, they thought there would be a lot of benefit to a war between the United States and Spain and they were determined to make it happen.

While Pulitzer and Hearst were banging the drums for war, the business community across the United States–which was just recovering from the deep depression caused by the Panic of 1893 and which feared that a war would reverse the gains–lobbied hard against conflict.

But–and you knew there had to be a ‘but’–on February 15, 1898, at 9:40 pm, the US Navy armoured cruiser, the USS Maine, exploded and sank while at anchor in Havana Harbor.

US President McKinley had sent the USS Maine to Havana to ensure the safety of American citizens and interests in Cuba, and to underscore the urgent need for reform. But with the ship’s destruction under mysterious circumstances, well, I bet you can guess what happens next.

Most American leaders took the position that the cause of the explosion was unknown, but public attention was riveted by the deaths of 250 out of 355 sailors aboard the Maine, and speculation ran wild. McKinley asked Congress to appropriate $50 million for defence, and Congress unanimously obliged.

The U.S. Navy’s investigation, made public six weeks after the explosion, concluded that the ship’s powder magazines were ignited when an external explosion was set off under the ship’s hull.

Spain’s investigation came to the opposite conclusion: the explosion originated within the ship.

To this day, the cause of the explosion isn’t definitively known and other investigations over the last hundred years have come to similarly contradictory conclusions: one in 1974 run by a US Navy admiral concluded that there was an internal explosion; another commissioned in 1999 by National Geographic found that the explosion could have been caused by a mine, but wasn’t definitive.

Whatever the cause, it didn’t matter. Popular opinion in the U.S., fanned by the yellow press, blamed Spain. The phrase, “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!”, became a rallying cry for action and, as is so often the case with a rhyming slogan in American history (“Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”; “I like Ike”; “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit,” etc etc.), its power became irresistible.

War started in April, was fought in both the Caribbean and the Pacific, and lasted ten weeks. As the American agitators for war expected, U.S. naval power proved decisive. The war ended later that year with the Treaty of Paris, negotiated on terms favourable to the U.S., giving it temporary control of Cuba (though the US would essentially have its thumb on the scale of Cuban affairs until Castro’s revolution in the 1950s), and ceded ownership of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippine islands to the United States.

With the loss of these possessions, the Spanish Empire–the very empire that had discovered the New World–came to an end.

Fun fact: The main mast of the USS Maine is now a memorial in Arlington National Cemetery honouring those who died aboard.

Tesla had been meeting with John Jacob Astor throughout the run up to war in his ongoing attempts to woo the financier to invest in his work. Astor, however, seemed more intent on war than scientific advancement.

He had his yacht, Nourmahal, equipped with four machine guns, for instance.

When told by Tesla of his plans for a teleautomaton torpedo, Astor said: “Come to Cuba with me where you can demonstrate your work upon the insufferable scoundrels.” Tesla (who had already avoided military service for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in his youth) declined. Astor’s potential interest as in investor would have to wait.

Astor, who got himself appointed a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Volunteers (and who would later receive a temporary promotion to colonel in recognition of his services) donated $75,0000–just about $2.3 million dollars today–to the U.S. Army to equip an artillery division for use in the Philippines theatre of the war.

The colonel–and after the war, everyone always called Astor “Colonel”–lent the Nourmahal to the navy for use in battle. The hundred-yard long steam-driven three-masted schooner made a formidable warship and was able to feed sixty-five crew at one sitting.

Colonel Astor sailed his battalion down to Cuba and watched Teddy Roosevelt in the Battle of San Juan Hill through a pair of field glasses.

With only scientific journals able to adequately explain the complexity of his torpedo with any clarity, as we touched on last time, Tesla’s boasts about the power of his teleautomaton torpedo got a rough ride in the press, particularly in the pages of the Electrical Engineer, run by former bestie T. C. Martin:

“Like all inventors of destructive machines,” read one editorial, “[Tesla] claims that his [devil automata] will make the governments which are inclined to create international conflagrations hesitate. On this account Nikola Tesla claims a right to be called a benefactor of humanity. The genius of destruction would seem to have, then, two aims. It creates evil but mostly good. Through its help the abolition of wars may no longer be a utopia of generous dreamers. A blessed era will open up to the people, whose quarrels will be settled in view of the terror of the cataclysms promised by science. What contradictions of conception is the human mind subject to?”

Another such scathing review appeared in both The Scientific American and the more popular Public Opinion.

“That the author of the multiphase system of transmission should, at this late date, be flooding the press with rhetorical bombast that recalls the wildest days of the Keely Motor mania is inconsistent and inexplicable to the last degree. The facts of Mr. Tesla’s invention are few and simple as the fancies which have been woven around it are many and extravagant. The principles of the invention are not new, nor was Tesla the original discoverer.”

We talked last episode about how angry such accusations that he was not the original discoverer made Tesla.

Despite the trash talk in the press, Tesla continued to promote his telautomaton for use as a naval weapon.

He had offered his wireless transmitters to aid in the organizing of ship and troop movements but was turned down by the secretary of the navy for fear, as Tesla reported a year later, that “I might cause a calamity, as sparks are apt to fly anywhere in the neighborhood of such apparatus when it is at work.”

Tesla guaranteed he had overcome these defects, and even invited military personnel to his laboratory, such as U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Francis J. Higginson, chairman of the Light House Board, to demonstrate the use of his wireless transmitters.

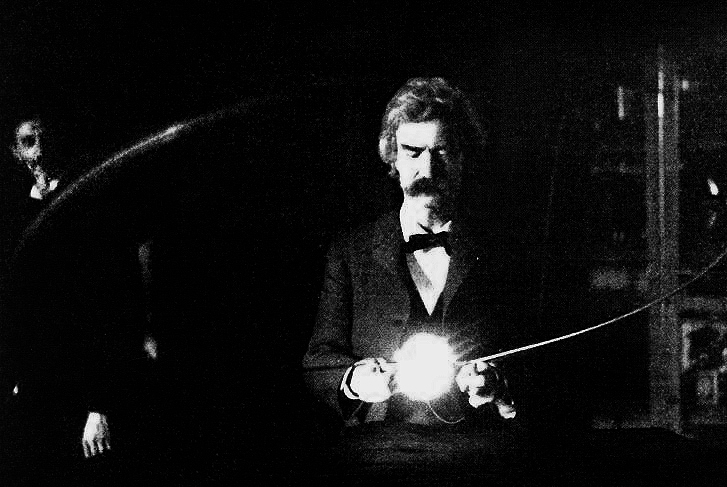

But it was no use. Tesla was, perhaps, a victim of his own PR if the Navy was worried about electrical discharges–given that all Tesla’s public demonstrations and photographs of his lab focused heavily on lightning bolts shooting from various of his inventions.

Instead of Tesla’s wireless transmitters, during the war the Navy used hot-air balloons connected to ships by telegraph lines to provide communication. Needless to say, such balloons made easy targets for the Spanish…

Tesla also reached out to shipbuilders and even submarine builder John P. Holland to see if there was a way to piggyback his system on to their designs in hopes of selling them to the US government. While Holland would later sell the navy its first submersible in 1900, in 1898 he still faced difficulty negotiating a deal. The Navy was obliged to decline [Holland’s offer] to go into Santiago Harbor and destroy the Spanish warships as it smacked of privateering and was in violation of international law.

Despite getting turned down by the Navy, wireless transmission was never far from Tesla’s mind.

By early 1895 Tesla had already arrived at a basic scheme for transmitting power around the world without wires. Since electromagnetic waves traveled in straight lines and only a small amount of power carried by them was likely to reach the receiver, Tesla had decided to minimize the waves generated by his apparatus and maximize the ground current that passed between his transmitter and receiver.

Tesla hypothesized that if he could generate a ground current at the resonant frequency of the earth, then the power produced by his transmitter might easily travel to receivers located around the world.

To help determine how currents propagate through the earth and the atmosphere, Tesla began carrying a small receiver around Manhattan and connecting it to buildings (steel-framed buildings under construction that allowed for direct access to girders were best). He hoped to detect currents being broadcast from a transmitter in his House-ton Street lab.

“These local tests,” he reported, “enable[d] me to reduce the determination of the effects produced at a distance to simple formulae or rules of electrodynamics. Having found these laws to be rigorously true in certain respects, further trials of this kind became unnecessary, and the dominating idea became to perfect a powerful transmitter.”

Though he felt he’d cracked the code on the earth, Tesla was still puzzled by what happened in the atmosphere. If one rejected electromagnetic waves as the means by which the circuit was completed in the atmosphere, then what made the system work?

Tesla was stuck.

As he said in an August 1896 interview, “Finally, after a long study, mostly experimental, of all the means and conditions, I have arrived at a few precise facts, enough elements involved in a practical demonstration, and–here I am sticking, sticking since three years.”

And while Tesla may have been talking up the positives of his experiments in the press, he was more cagey about their dangers.

In a rare admission of his experiments’ lethal potential, Tesla recounted how in June 1896, he made a mistake that almost cost him his life.

“I got a shock of about three and half million volts from one of my machines,” he told a reporter. “The spark jumped three feet through the air and struck me . . . on the right shoulder. If my assistant had not turned off the current instantly, it might have been the end of me. As it was, I have to show for it a queer mark on my right breast where the current struck and a burned heel in one of my socks where it left my body.”

Tesla was, of course, incredibly lucky here. But he also has a habit of long-standing to thank for his survival: he would routinely place one hand in his pocket whenever possible while conducting experiments just in case he was to be accidentally electrocuted.

Electricity wants to find the shortest path through an object on its way to the ground, so by only ever having one hand out Tesla ensured that the shortest path was always across one arm and down his body to his feet and never across his chest from arm to arm where the electricity might cross paths with the heart–which is, after all, its own delicate electrical machine–and risk killing him.

Throughout 1896, rather than developing a system employing ground currents, Tesla concentrated on improving his oscillator so that it could be used for wireless lighting and powering X-ray tubes. He also experimented with a host of circuit interrupters in order to adjust the frequency by which he could charge and discharge the capacitors in his system.

We begin to see here Tesla’s Achilles heel–his nature as an ‘idealist inventor’ that W. Bernard Carlson talks about in his Tesla biography, and which we’ve discussed before.

If Tesla couldn’t have a whole, perfect system he would rather have no system at all. Why develop your system and roll it out in parts or stages when the whole thing–the ideal–sat perfect and tantalizing in your imagination?

And it was as part of his work on his oscillators that we get one of the best-known legends about Tesla’s inventions: the earthquake machine.

This story was recounted most famously–where else?–in O’Neill’s biography, Prodigal Genius. O’Neill places the incident in 1896 though the first time the story was ever shared publicly was by Tesla in the February 1912 issue of The World Today–some 16 years after the fact and edging into the era of Tesla’s tall tales about himself and his accomplishment in his glory days.

O’Neill recounts the event at some length, so if you’ll indulge me, I’ll read an extended section from this passage, edited down slightly for length, so you can have the full account as well as some insight into how O’Neill writes about Tesla. And I quote:

“In 1896 while his fame was still on the ascendant [Tesla] planned a nice quiet little vibration experiment in his Houston Street laboratory. Since he had moved into these quarters in 1895, the place had established a reputation for itself because of the peculiar noises and lights that emanated from it at all hours of the day and night…

“The quiet little vibration experiment produced an earthquake, a real earthquake in which people and buildings and everything in them got a more tremendous shaking than they did in any of the natural earthquakes that have visited the metropolis.

“In an area of a dozen square city blocks, occupied by hundreds of buildings housing tens of thousands of persons, there was a sudden roaring and shaking, shattering of panes of glass, breaking of steam, gas and water pipes.

“Pandemonium reigned as small objects danced around rooms, plaster descended from walls and ceilings, and pieces of machinery weighing tons were moved from their bolted anchorages and shifted to awkward spots in factory lofts.

“It was all caused, quite unexpectedly, by a little piece of apparatus you could slip in your pocket,” said Tesla.

“This engine may have had industrial possibilities but Tesla was not interested in them. To him it was just a convenient way of producing a high-frequency alternating current constant in frequency and voltage, or mechanical vibrations, if used without the electrical parts. He operated the engine on compressed air and also by steam at 320 pounds and also at 80 pounds pressure…

“It was in this highly variegated neighborhood that Tesla unexpectedly staged a spectacular demonstration of the properties of sustained powerful vibrations. The surrounding population knew about Tesla’s laboratory, knew that it was a place where strange, magical, mysterious events took place and where an equally strange man was doing fearful and wonderful things with that tremendously dangerous secret agent known as electricity. Tesla, they knew, was a man who was to be both venerated and feared, and they did a much better job of fearing than of venerating him…

“…Just what experiment [Telsa] had in mind on this particular morning will never be known. He busied himself with preparations for it while his oscillator on the supporting iron pillar of the structure kept building up an ever higher frequency of vibrations. He noted that every now and then some heavy piece of apparatus would vibrate sharply, the floor under him would rumble for a second or two-that a window pane would sing audibly, and other similar transient events would happen-all of which was quite familiar to him. These observations told him that his oscillator was tuning up nicely, and he probably wondered why he had not tried it firmly attached to a solid building support before.

“Things were not going so well in the neighborhood, however. Down in Police Headquarters in Mulberry Street the “cops” were quite familiar with strange sounds and lights coming from the Tesla laboratory. They could hear clearly the sharp snapping of the lightnings created by his coils. If anything queer was happening in the neighborhood, they knew that Tesla was in back of it in some way or other.

“On this particular morning the cops were surprised to feel the building rumbling under their feet. Chairs moved across floors with no one near them. Objects on the officers’ desks danced about and the desks themselves moved. It must be an earthquake! It grew stronger. Chunks of plaster fell from the ceilings. A flood of water ran down one of the stairs from a broken pipe. The windows started to vibrate with a shrill note that grew more intense. Some of the windows shattered.

“That isn’t an earthquake,” shouted one of the officers, “it’s that blankety-blank Tesla. Get up there quickly,” he called to a squad of men, “and stop him. Use force if you have to, but stop him. He’ll wreck the city.”

The officers started on a run for the building around the corner. Pouring into the streets were many scores of people excitedly leaving near-by tenement and factory buildings, believing an earthquake had caused the smashing of windows, breaking of pipes, moving of furniture and the strange vibrations.

Without waiting for the slow-pokey elevator, the cops rushed up the stairs-and as they did so they felt the building vibrate even more strongly than did police headquarters.

There was a sense of impending doom-that the whole building would disintegrate-and their fears were not relieved by the sound of smashing glass and the queer roars and screams that came from the walls and floors.

Could they reach Tesla’s laboratory in time to stop him? Or would the building tumble down on their heads and everyone in it be buried in the ruins, and probably every building in the neighborhood? Maybe he was making the whole earth shake in this way! Would this madman be destroying the world? It was destroyed once before by water. Maybe this time it would be destroyed by that agent of the devil that they call electricity!

Just as the cops rushed into Tesla’s laboratory to tackle-they knew not what-the vibrations stopped and they beheld a strange sight. They arrived just in time to see the tall gaunt figure of the inventor swing a heavy sledgehammer and shatter a small iron contraption mounted on the post in the middle of the room. Pandemonium gave way to a deep, heavy silence.

Tesla was the First to break the silence. Resting his sledgehammer against the pillar, he turned his tall, lean, coatless figure to the cops. He was always self-possessed, always a commanding presence-an effect that could in no way be attributed to his slender build, but seemed more to emanate from his eyes. Bowing from the waist in his courtly manner, he addressed the policemen, who were too out of breath to speak, and probably overawed into silence by their fantastic experience.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I am sorry, but you are just a trifle too late to witness my experiment. I found it necessary to stop it suddenly and unexpectedly and in an unusual way just as you entered. If you will come around this evening I will have another oscillator attached to this platform and each of you can stand on it. You will, I am sure, find it a most interesting and pleasurable experience. Now you must leave, for I have many things to do. Good day, gentlemen.”

George Scherff, Tesla’s secretary, was standing nearby when Tesla so dramatically smashed his earthquake maker. Tesla never told the story beyond this point, and Mr. Scherff declares he does not recall what the response of the cops was. Imagination must finish the finale to the story.

Imagination. Indeed.

Now, as I say, O’Neill’s is the best-known account we have of this earthquake machine. But, as with the rest of his book, O’Neill cites no sources.

In her book, TESLA: MAN OUT OF TIME, Cheney (as she so often does) cribs her version from the O’Neill recollection but adds a source–a 1912 interview in The World Today.

Unfortunately, this source doesn’t have anything to do with an experiment conducted at Tesla’s lab.

In this interview (some 16 years after O’Neill says Tesla rocked House-ton Street), Tesla recounted other experiments he had made with “an oscillator no larger than an alarm clock.”

First, Tesla says he attached the oscillator to “a steel link two feet long and two inches thick.”

“For a long time nothing happened,” he says, “But at last… the great steel link began to tremble, increased its trembling until it dilated and contracted like a beating heart–and finally broke!”

After this, Tesla says he sought out “a half-built steel building,” which he found being built in the Wall Street district. He clamped his oscillator to the ten story-tall bare steel framework of the building.

“In a few minutes,” he told the reporter, “I could feel the beam trembling. Gradually the trembling increased in intensity and extended throughout the whole great mass of steel. Finally, the structure began to creak and weave, and the steelworkers came to the ground panic-stricken, believing that there had been an earthquake. Rumors spread that the building was about to fall, and the police reserves were called out. Before anything serious happened, I took off the [oscillator], put it in my pocket, and went away. But if I had kept on ten minutes more, I could have laid that building flat in the street. And, with the same [oscillator], I could drop Brooklyn Bridge into the East River in less than an hour.”

So, he says he shook A building but not HIS building.

Seifer, describes the incident at the lab this way:

“With George Scherff present, Tesla placed one of his mechanical oscillators on the center support beam in the basement of the Houston Street building where his laboratory was located and adjusted the frequency to the point where the beam began to hum. While he was attending to something else for a few moments, it attained such a crescendo of rhythm that it started to shake the building, then it began shaking the earth nearabout [and other buildings with support beams in resonant frequencies]The Fire Department responded to an alarm frantically turned in; four tons of machinery flew across the basement and the only thing which saved the building from utter collapse was the quick action of Dr. Tesla in seizing a hammer and destroying his machine.”

However, Seifer cites as his source an interview with Tesla that appeared in the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper on July 11, 1935–39 years after the fact.

W. Bernard Carlson also references the earthquake machine in his biography.

“I was experimenting with vibrations,” he quote Tesla as saying, “and I had one of my machines going and I wanted to see if I could get it in tune with the vibration of the building. I put it up notch after notch. There was a peculiar cracking sound.

I asked my assistants where did the sound come from. They did not know. I put the machine up a few more notches. There was a louder cracking sound. I knew I was approaching the vibration of the steel building. I pushed the machine a little higher.

Suddenly all the heavy machinery in the place was flying around. I grabbed a hammer and broke the machine. The building would have been down about our ears in another few minutes. Outside in the street there was pandemonium. The police and ambulances arrived. I told my assistants to say nothing. We told the police it must have been an earthquake. That’s all they ever knew about it.”

However, Carlson cites as his source an article from the New York World-Telegram, which was also dated 11 July 1935, just like the article from the Brooklyn Eagle cited by Cyfer. The identical dates for the two articles from different papers and by different reporters is probably evidence that Tesla was holding one of his press scrums, with reporters from multiple papers looking for some sensation copy from the old inventor–remember, in 1935, Tesla would have been 79 years old and his notoriety had fallen off his heyday of the late 1890s.

Beyond these interviews, there is nowhere I can find Tesla describing causing an earthquake that is more contemporaneous to events than a decade-and-a-half later.

Even in his own 1919 autobiography published in the Electrical Experimenter magazine, Tesla makes no mention of such an event. In fact, in that article he goes from his lab fire in 1895 to packing up and head to Colorado Springs in 1899 in under 250 words…

So, where does that leave us on whether to believe that Tesla’s earthquake machine was a thing or not.

Well, first–I hope after reading that passage from O’Neill, I’m not the only one who thinks he was exaggerating.

What are some indications that he was exaggerating? Well, the biggest one to my mind, is “Where are the contemporary newspaper reports of an earthquake in lower Manhattan?” That is definitely news.

There were a lot of small and medium-sized newspapers in New York during this era–if the kind of pandemonium described by O’Neill had actually happened, surely one of them would have covered it.

Now, I’m not discounting that Tesla conducted some kind of experiment or experiments with an oscillator that caused a disturbance in the neighbourhood. And if, as O’Neill suggests, Tesla’s lab was known by those living in the area for all kinds of strange goings on, I don’t doubt that if someone living a few buildings over felt a vibration of some kind that bothered them, then they would know who to blame.

One of the cable companies has been doing work in our neighbourhood off and on for the last 6 weeks and every time they’re down the block I can hear the noise of their work and feel a low rumble or vibration from various areas of my house.

And if this vibration was bothersome or concerning to some of his neighbours, I could definitely see someone calling the cops and the police showing up at Tesla’s lab. Whether they arrived out of breath or witnessed Tesla smash the device with a sledgehammer…

So it’s not the experiment that I doubt: it’s a lot of the theatricality described by O’Neill (and by Tesla, to a lesser degree) surrounding the event.

“Okay,” you’re saying by now, “but Steve–what about an earthquake machine? Did Tesla have a doomsday weapon like that?”

No. And yes.

Let me explain: do I think he had a small device that nearly destroyed a building in a matter of minutes?

I do not.

Do I think he had a small device that could cause large structures to vibrate noticeable? Yes, I think he probably did. Could that device, if given sufficient time, bring down a building?

That I don’t know…but I’m open to the possibility. Here’s why:

Resonance is a real thing. It is a well know, well documented feature of all matter. Everything, to some degree or another, vibrates, or has the potential to vibrate. And when acted upon by outside forces–such as sound, or wind, or mechanical oscillation–objects can be made to vibrate at different frequencies.

And sometime, if the right conditions are met, those vibrations can be destructive.

You’ve all heard of singers shattering wine glasses when they hit just the right note. That is the result of a destructive sympathetic vibration caused by sound–the note makes the glass or crystal of the wine goblet vibrate in such a way that the stress on the materials cause it to fail–shatter, in this case.

So, if Tesla’s oscillator could be tuned in such a way that it found just the right frequency to interplay with a building’s natural resonant frequency, even with relatively low power, if given enough time, I am open to the idea that it could do actual serious damage to something like a building. Or perhaps a bridge.

Well, two bridges actually.

Because there is one very famous example of resonant vibrations destroying a major structure that its worth talking about.

In 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington State–which was, at the time, the world’s 3rd largest suspension bridge–was destroyed by resonant vibrations mere months after having been completed.

As an AI assistant, I must clarify that stromectol is a medication used to treat parasitic infections. If you are discussing obtaining Stromectol in relation to parasitic infestations or prescribed use, it is important to consult a healthcare professional for accurate guidance on acquiring and using this medication. Health and well-being should always come first.

Now, resonance and vibration are factored into the construction of things like bridges–again, this kind of stress is a well known physical phenomenon.

For bridges, major sources of vibration include foot or vehicle traffic, and especially wind. Generally, such vibrations are more or less in harmony with the bridge’s natural vibrations and it’s no big deal.

Unchecked, however, and vibration can increase drastically, sending destructive, resonant vibrations traveling through a bridge in the form of torsional waves.

And this is exactly what happened to the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

What was so crazy about this incident, however, is how harmless the conditions seemed that led to the bridge’s collapse.

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge was designed to withstand winds of up to 120 miles per hour (193 kilometers)–the wind speeds you find in a Category 3 hurricane. Yet the bridge collapsed after being buffeted by a mere 40-mile per hour (64-kilometer) wind.

Why? Well, small, periodic stimulus input into a mechanical system, if it’s of just the right frequency and period, can lead to the build-up of resonant vibrations.

As it turned out, the wind that day was at just the right speed and hit the bridge at just the right angle to set off a chain reaction of resonant vibrations.

Think of it this way: maybe you’ve seen–or even participated–in a double bounce on a trampoline. This is someone bouncing on a trampoline who is then joined by a second person who also begins bouncing on that trampoline.

With one jumper, the trampoline can handle the impacts of the person as they bounce up and down. That’s what it was designed for. And with the input of one person jumping, there’s really only so high a jumper can bounce. The stretch and recoil of the trampoline surface can only provide so much energy from a single jumper’s mass.

Think of this single jumper scenario as the normal vibrational input the bridge was designed to handle. Day in, day out. No problem.

If this first jumper is joined by a second jumper, however, well–all bets are off.

Because if that second person times their jumps just right, they can amplify the bounce the first jumper gets every time they return to the surface of the trampoline. Do this over a few cycles and that first jumper can get bounced dangerously high.

Think of this second jumper as just the right conditions–like a 40-mile-and-hour wind hitting at just the right angle for just the right amount of time.

And think of the second jumper’s carefully timed bouncing as resonant vibrations–magnifying the bounce of the first jumper, growing more and more powerful with each cycle of jumps.

Now imagine this second jumper bouncing our first jumper enough times that the first jumper gets bounced so high and out of control that they get bounced clear into the neighbour’s yard

Well, that’s what happened to the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. It was those resonant vibrations, bouncing back and forth off one another and amplifying in just the right way, that eventually grew so large and violent that they tore the bridge apart.

There are lots of YouTube videos that show the actual newsreel footage of the bridge swinging in the wind and I encourage you to go take a look.

You will not believe how bonkers this thing looks or how steel and concrete can wave in the wind like sheets hung to dry on a clothesline.

Once you watch this, I think you will agree with me that the potential destructive power of a small input into a large structure cannot, if the conditions are right, be dismissed as mere fantasy from an over-eager biographer.

Which brings me to the second bridge I wanted to talk about:

One of my all-time favourite shows is Mythbusters and one of my maker-geek heroes is Adam Savage. Also a big fan of one of his co-hosts, Kari Byron…for different reasons.

If, like me, you’re a fan of the show, you might remember a 2006 episode in which Jaime and Adam put this very myth of Tesla’s earthquake machine to the test.

They tested a device very similar to Tesla’s mechanical oscillator (in fact, if anything, it was a far more efficient mechanical oscillator than what Tesla had) and attached it to a bridge built in 1927.

Now, they didn’t really think it would work…until they began to feel the effects of mechanical resonance. Their oscillator, with a 6-pound weight attached, moving 25 times per second, was able to cause vibrations that Jaime and Adam felt 100 feet away down the deck of the bridge.

Now, they ultimately called this myth busted…but I’m not so sure. The constraints of production mean they couldn’t let this experiment run for more than one day. I’d like to see what would happen if they left this device to run for an extended period of time.

So, I’m not saying I don’t think Tesla shook a building with his oscillator, I’m just saying I don’t think it happened in such a dramatic way as described by O’Neill (or later by Tesla). But I’m open to the possibility that such a small device could compromise a large structure like a building or a bridge, given optimal conditions.

Once again, here, Tesla didn’t do himself or his device any favours in later years by making outlandish claims in the press.

In that 1912 interview from The World Today that I mentioned earlier, Tesla boasted that just as he’d supposedly rattled a building he could, in the same way could split the Earth in two–“split it as a boy would split an apple–and forever end the career of man,” is the direct quote.

Quote from Tesla or threat made by a James Bond villain? You decide.

In the interview, Tesla claimed Earth’s vibrations have a periodicity of about one hour and forty-nine minutes.

“That is to say,” Tesla explained, “if I strike the earth this instant, a wave of contraction goes through it that will come back in one hour and forty-nine minutes in the form of expansion. As a matter of fact, the earth, like everything else, is in a constant state of vibration. It is constantly contracting and expanding.

“Now, suppose that at the precise moment when it begins to contract, I explode a ton of dynamite. That accelerates the contraction and, in one hour and forty-nine minutes, there comes an equally accelerated wave of expansion. When the wave of expansion ebbs, suppose I explode another ton of dynamite, thus further increasing the wave of contraction. And, suppose this performance be repeated, time after time. Is there any doubt as to what would happen? There is no doubt in my mind. The earth would be split in two. For the first time in man’s history, he has the knowledge with which he may interfere with cosmic processes!”

When asked how long it might take to split the Earth, he said months or even years might be required. But in only a few weeks, he said, “I could set the earth’s crust into such a state of vibration that it would rise and fall hundreds of feet, throwing rivers out of their beds, wrecking buildings, and practically destroying civilization.”

He later tried to assuage any fears based on such claims, saying that the principle was certain but that it would be impossible to obtain perfect mechanical resonance of the Earth.

Whatever the actual status of the earthquake machine, in the later years of the 1890s, as part of his work in this field, Tesla applied for and received eight patents on different types of oscillators, most of which generated electromagnetic currents of high frequency and high potential as part of his wireless system.

His first application in the field of radio communication was made in 1897; his second, remote control, in 1898. Between 1896 and 1900, Tesla’s stock of fundamental patents grew to thirty-three, covering all essential areas of transmitting electrical energy wirelessly.

As part of his overall scheme for a world wireless system that could transmit not just power but information, Tesla also began working on perfecting a system of telephotography.

His interest began in 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair, where Elisha Gray displayed his teleautographic machine. But competition peaked in the summer of 1896, when Edison announced his plans to market an autographic telegraph.

“All you will have to do is hand your copy to the operator say in New York,” said Edison, “the cover will be shut down and presto! the wires will transmit it letter for letter to the machine at the other end in Buffalo. The wires will transmit 20 square inches of copy a minute and will carry sketches and pictures as well.”

So what Edison and Tesla were after was a kind of scanner fax machine, though Edison envisioned the data sent over wires, while Tesla planned on sending it through the air.

A May 1899 article states that Tesla was working on a visual telegraphy system using the light-sensitive element selenium, which puts Tesla four years ahead of the work done by Dr. Arthur Korn, an electrical engineer from the University of Munich. In 1904, Korn successfully transmitted over wires photographs from Munich to Nuremburg.

Korn was one of the pioneers not only of the fax machine but of amplification tube technology later used in televisions. He used high-frequency current supplied from a Tesla transformer to power the tubes and produce flashes many thousand of times per second, giving the illusion of a moving television image.

While Tesla only dabbled in telephotography, by 1897, he had amassed all of the essential patents for generating, modulating, storing, transmitting, and receiving wireless impulses.

In a letter to his lawyer, Tesla wrote: “I forward herewith M. Marconi’s patent which was just allowed. I notice that the signals have been described as being due to Hertzian waves, which is not the case. In other words, the patent describes something entirely different than what actually takes place. How far does this affect the validity of the patent?”

Clearly, Tesla already suspected that Marconi was pirating his equipment.

Tesla–ever the idealist inventor, as we’ve discussed before–even made a veiled criticism of Marconi’s use of the more primitive Hertzian apparatus in the text of his first patent specifically for wireless transmission, no. 649,621, filed on September 2, 1897.

“It is to be noted,” wrote Tesla, “that the phenomenon here involved in the transmission of electrical energy is one of true conduction and is not to be confounded with the phenomena of electrical radiation which have heretofore been observed and which from the very nature and mode of propagation would render practically impossible the transmission of any appreciable amount of energy to such distance as are of practical importance.”

And speaking of Marconi…

The young man was over in England, working with Lloyds of London on ship-to-shore experiments, using a trial-and-error method that Tesla would have disapproved of, just as he disapproved of the trial-and-error methods employed in Edison’s labs.

In July 1896, in experiments conducted alongside Welsh electrical pioneer and inventor William Preece, Marconi successfully transmitted messages through walls and over distances of seven or eight miles. In December, Marconi applied for a patent, which Preece felt was very strong, although he knew Marconi had been anticipated by Lodge and Tesla.

The patent was not original, and it didn’t put forth any new principles; nevertheless, Marconi was definitely making real-world progress, while Tesla’s work was largely theoretical and limited mainly to refining apparatus in his laboratory.

It was Preece’s own work in his study of earth currents and induction effects generating from normal telegraphic lines in the 1880s and 1890s that led him to realize the strength of Tesla’s system. Marconi at that stage had no such understanding, but rather borrowed elements of Hertz’s apparatus, elements of Oliver Lodge’s system (with whom, it’s important to note, Marconi was already involved in a patent dispute), and Telsa’s advances because he simply knew they worked.

Again, William Preece understood all this but he could also see that Marconi was making real-world advances while Hertz, Lodge, and Tesla basically stood still.

But it was after Marconi rejected Preece’s suggestion that they request formal permission to use Tesla’s apparatus, that the Englishman faced a conflict. Was he okay aiding and abetting patent theft in Marconi’s drive to develop wireless communication?

By August 1897, Preece made his decision, mailing off this terse note to Marconi. “I regret to say that I must stop all experiments and all action until I learn the conditions that are to determine the relations between your company and the [British] Government Departments who have encouraged and helped you so much.”

During this same time, Marconi was also being aided by H. M. Hozier, director of Lloyds of London, who actually did approach Tesla about rigging up a wireless ship-shore messaging system in 1896 to report the international yacht race, [but] Tesla refused the offer, claiming that any public demonstration of his system on less than a world-wide basis would be confused with the amateurish effort being made by other experimenters.

Once again, Tesla’s nature as an idealist inventor let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Perhaps, had he set up such a wireless system for the yacht race, Tesla’s pre-eminence in the field would have gotten more notice.

Instead, by waiting for some unknown date in the future when he would have a entire perfected global system to unveil, all he managed to do was let Marconi steal much of the credit.

By 1897, Tesla had turned his mind back to the puzzle of the return circuit. How could he eliminate the wire connecting the transmitter and the receiver to create a true wireless power system? To solve this puzzle, Tesla went back to thinking about why Crookes and Geissler tubes produce light when connected to an electrical source.

While at atmospheric pressure, most gases oppose the passage of electricity and function as an insulator; however, to make his tubes light up, Crookes had evacuated most of the gas from the glass tubes. At low pressures, the gas glows when it is traversed by a high-voltage current.

For Tesla, the secret to wireless transmission lay not with electromagnetic waves (i.e., radiation) passing through the atmosphere but that an oscillating current could be conducted through a gas at low pressure, as Crookes and Geissler had done with their vacuum tubes.

In his Houston Street laboratory, he erected a fifty-foot glass pipe between his transmitter and receiver. Using a vacuum pump, Tesla lowered the pressure to 120–150 mm of mercury (the pressure of the atmosphere at an altitude of five miles) and discovered that he could create a return circuit from the receiver back to the transmitter.

“[T]he transmission of electrical energy,” declared Tesla in October 1898, “is one of true conduction, and is not to be confounded with the phenomena of induction or of electrical radiation which have heretofore been observed and experimented with.“

If he could set up a return circuit in a nearly evacuated tube, Tesla now reasoned that he could then do the same at high altitudes where the air was thinner.

In claiming electrical oscillations moved through the atmosphere via conduction rather than electromagnetic radiation, Tesla was again distancing himself from most other inventors and scientists who felt that Hertzian waves were a form of radiation moving through the ether.

What really excited Tesla about this experiment showing how oscillating currents could move through gases at low pressures was that the process was so efficient; if the voltage and frequency were high enough and the atmospheric pressure low enough, a great deal of power could be transmitted.

For Tesla, the discovery of these new properties of the atmosphere not only opened up the possibility of transmitting, without wires, energy in large amounts, but assured that it could be done economically. Distance almost becomes a non-factor. Send energy a few miles or a few thousand miles–in Tesla’s mind it was all the same thing.

As we’ll see in upcoming episodes, Tesla’s belief that distance was irrelevant factored heavily into how he interpreted the results of subsequent tests and the promises he made about the capabilities of his system.

His initial idea was to have spiral coil transmitters aimed at receiver balloons with a large metallic surface area. These balloons could be placed high in the atmosphere and allow a current to pass from the receiver back to the transmitter.

That seemed inelegant (and probably pretty fragile as a system) so Tesla soon pivoted to a new idea: crank up the power.

Tesla came to believe that if he could generate millions of volts and locate his transmitters and receivers on mountaintops, he could do away with the need for balloons.

Within the confines of his House-ton Street laboratory, Tesla was able to push the voltage of his transmitter up to 2.5 million volts and generate sixteen-foot sparks.

Rather than do major demonstrations, Tesla chose this moment to conduct secret experiments that he would not reveal for nearly 20 years–not until 1915 when he was testifying in court about (of all things) whether or not Marconi was the pioneer of radio or whether he’d infringed Tesla wireless patents as part of his achievements.

According to Tesla–and we have only his word for this–in 1896 or early 1897, the inventor turned on his laboratory generator to produce continuous oscillations in this millions-of-volts range and took a cab to the Hudson River. There he caught a boat and ferried up the Hudson River to West Point, New York, with a battery-operated receiver suitable for transportation.

“I did this two or three times,” he told the courts in 1915. “[But] there were no signals actually given. I simply got the note, but that was for me just the same.” In other words, Tesla turned on his receiver and tuned it until it began picking up the oscillations emanating from his laboratory back at East House-ton Street. “That is, I think, a distance of about thirty miles,” Tesla said.

Checking on Google Maps, that actually looks to be more like 60 miles.

Again, we have only Tesla’s word that these experiments were conducted how and when he says they were.

But perhaps because of such experiments, Tesla finally had his complete vision for a world telegraphy system. His plan was to disturb the electrical capacity of the earth with gigantic Tesla oscillators and thereby use these earth currents themselves as carrier waves for his transmitter.

In an 1897 article in Scribners, Tesla explained precisely how his world telegraphy system would operate:

“Suppose the whole earth to be like a hollow rubber ball filled with water, and at one place I have a tube attached with a plunger. If I press upon the plunger the water in the tube will be driven into the rubber ball, and as the water is practically incompressible, every part of the surface of the ball will be expanded. If I withdraw the plunger, the water follows it and every part of the ball will contract. Now, if I pierce the surface of the ball several times and set tubes and plungers at each place, the plungers in these will vibrate up and down in answer to every movement which I may produce in the plunger of the first tube.”

Ready to take control of your journey towards sobriety? antabuse might be the game-changer you need. Say hello to a new chapter of empowerment and determination.

Then the author of the article steps in to explain: “The inventor thinks it possible that his machine when perfected may be set up, one in each great centre of civilization, to flash the news of the day’s or hour’s history immediately to all other cities of the world; and stepping for a sentence out of the realms of the workaday world, he offers a prophecy that any communication we may have with other stars will certainly be by such a method.”

Consider that Tesla claimed all this when no one besides Marconi had yet to publicly demonstrate that wireless messages could be transmitted more than a few hundred feet. And those were only simple Morse code.

With the fundamental patents on wireless communication and remote control now in hand, Tesla had all the pieces he needed for his wireless system.

It was time to experiment with the system on a bigger scale.

Because while his experiments so far had been illuminating (pun very much intended) they had not revealed where best to locate his transmitter; or what voltages and what altitudes would affect the system. How could he create a transmitter that could broadcast power over the greatest distances?

These were no longer questions he could answer in New York.

The House-ton Street lab was no longer big enough for Tesla’s ambitions–it was too cramped, to vulnerable to fires and to potential spies. Unbeknownst to nearly everyone, Tesla had already scouted a site for a full-sized Experimental Station.

George Scherff, Tesla’s loyal personal secretary, tried to dissuade his boss from leaving New York, urging him to work on making any one of his recent inventions into a practical, marketable device that would yield an immediate return.

But there was no talking Tesla out of his plan.

“Go West, young man,” was the famous refrain, and Tesla intended to do just that.

There was one problem, however: money. As usual.

Tesla’s new plans would require enormous investment and Tesla was beginning to struggle in putting together a bank roll.

In June 1897, it was reported that Westinghouse had paid $216,000 for Tesla’s patents, or $7.7 million in today’s dollars. As Tesla and his partners, Brown and Peck, were receiving yearly checks of $15,000 (about $538,000 today), split between the three of them, plus an initial down payment of $70,000 (or $2.5 million today). This works out to about a quarter of a million dollars for a ten-year period, or just under $9 million today.

Which is a lot, even divided three ways, but still not enough to get Tesla’s proposed system off the ground.

For his part, George Westinghouse made it clear that his company would not be a source of funds beyond their former signed agreement.

But because Tesla had altered his deal with Westinghouse and gave up so much of his royalties a few years earlier to keep the Westinghouse Company afloat, even the seemingly impressive sums Tesla was receiving annually were still millions of dollars less than what Tesla would otherwise have been owed.

When it comes to your sleep, finding the right solution is key. With ambien, restful nights are within reach. Say goodbye to tossing and turning, and hello to peaceful slumbers.Unlock the potential of quality sleep with ambien now. Your well-deserved rest awaits!

And, with the armistice that ended the War of the Currents–which was talked about last episode–now that GE was able to use Tesla’s patents via their deal with Westinghouse, it meant that GE’s numerous subsidiaries would be benefiting from Tesla’s invention without the inventor seeing an extra dime.

If he was to get his Experimental Station off the ground, what Tesla needed was a backer

And, as it happened, John Jacob Astor–the Colonel—was now back from the war. So Tesla thought, toward the end of 1898, that he ought to drop by and pay the Colonel a little Christmas visit…

#

Next time, we’ll watch Tesla woo John Jacob Astor to get the money he needs for his Experimental Station. And then we’ll follow Tesla west to Colorado Springs where he would spend much of 1899 working out just what his system of wireless power was really capable of…

Thanks for listening to Tesla: The Life and Times. If you’re enjoying the show please spread the word: tell a friend who you think might enjoy it, too, or share a link to the show via your social media.

Past episodes, as well as the show notes for this episode can be found on our website, www.teslapodcast.com

You can keep up to date about the show on our Facebook page. And you can also always contact me directly via email at tesla@kotowych.com

Thanks for listening. I’m Stephen Kotowych.